The CODE for building participatory and ethical data projects

What’s the best strategy for ensuring development projects adhere to ethical guidelines? This is a complex question as answers will vary by sector and context. Yet ethical issues such as bias, representativeness, and data availability and quality have direct impacts on development projects. Ethics and solid governance mechanisms that center community engagement must sit at the heart of these projects for them to be successful, sustainable and transformative.

In the seven years since Data-Pop Alliance’s work began, numerous learnings have led us to rethink our processes. As a result, most of our projects since 2020 include a Council for the Orientation of Development and Ethics (CODE). (See this 2020-2022 report for more information on CODEs.)

Building collaborative projects using the CODE

A CODE is a group of independent stakeholders who voluntarily share their expertise in areas of direct relevance to a project. As an advisory group, it provides oversight to ensure a project abides by key ethical principles including fair and safe use of data and local context-specific concerns. CODE responsibilities vary slightly based on project needs but generally include the following:

- Driving the creation, function and application of the legal conditions of project governance, including counseling on privacy-related issues such as access to and use of data, use of algorithms, biases, legal compliance, user authorization and community engagement.

- Improving the local relevance of the project including by suggesting ways to enhance project benefits and visibility and improve outreach to relevant groups.

- Recommending improvements to methodology and data sources and guiding development of a balanced and inclusive local data ecosystem.

- Advising on sensitive use cases and potential risks to intended target communities.

- Functioning as a forum for dispute resolution and community complaints regarding data use and engaging concerned stakeholders across sectors.

- Identifying strategies for a project’s future, including scaling, broader application and improvements to project design.

Though the advisory role of the CODE is not legally binding, project staff give considerable weight to CODE members' feedback, integrating their recommendations whenever possible. As with any group of volunteers, CODEs will face challenges, from spotty meeting attendance to low levels of participation. Effective planning early in the project, preparation and active moderation are key ingredients to ‘healthy’ and impactful CODEs.

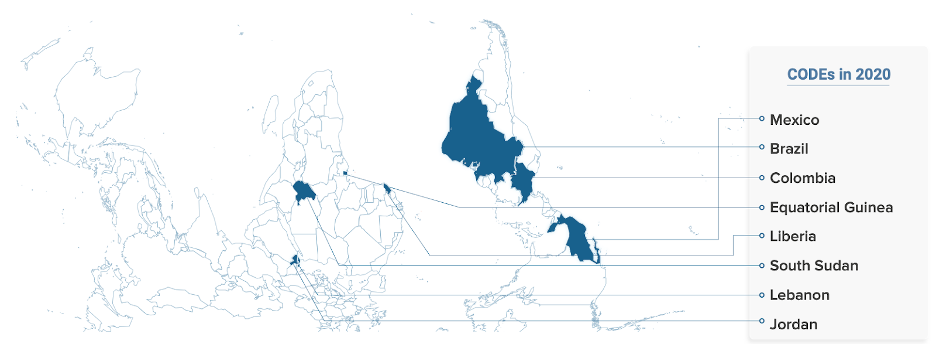

CODEs are typically composed of 10 local experts representing academia, civil society, government and private enterprise. Data-Pop Alliance implemented CODEs last year in eight countries (shown in Figure 1). Most CODE meetings have been held virtually due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The CODE concept was born during the initial implementation of the Open Algorithms (OPAL) project, a data sharing initiative co-founded by Data-Pop Alliance that aims to unlock the potential of private sector data for public good in a privacy-preserving, participatory and sustainable manner.

Figure 1: Data-Pop Alliance implemented CODEs in Latin and South America, Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East in 2020.

The CODE in practice: Gender-based violence in Latin America

CODEs often steer projects in a new direction. We saw this with a recent project that aimed to identify personal and environmental factors associated with domestic violence reporting rates in three countries. This project required us to access data from government agencies providing services to survivors (police reports, hotline records, counseling and legal support centers, etc.) as well as from national surveys on family violence. Researchers used this data to map domestic violence reporting rates at the district level in three cities to analyze relationships between reporting rates and environmental risk factors.

Data-Pop Alliance set up three CODEs in Mexico City, Bogotá and São Paulo for the project, which was funded and supported by the GIZ Data Lab and the Unidas network between 2020 and early 2021. Involving the CODES early in the project resulted in a dramatic shift in our research focus and design that led to the production of meaningful and locally-relevant research while minimizing harm to individuals and communities.

Project leaders and CODE members established ethical guidelines for research and data management following best practices in the field including: (1) Non-maleficence or no-harm, (2) de-stigmatization, (3) confidentiality and privacy, (4) lawful, legitimate and fair use of and access to data, and (5) data quality and transparency. Consultation with the CODEs, however, quickly shifted our perspective on the ethics of the original project design.

Our initial goal had been to create maps of domestic violence “hotspots” in the selected cities. Through periodic, virtual meetings with project CODEs, we realized that mapping geographical areas with higher rates of domestic violence posed a considerable risk of stigmatization to communities and individuals. Our team modified the project’s aim to avoid replicating long-standing discriminatory narratives about groups of people and geographical areas—a process that also incorporated suggestions from CODE members.

While we anticipated issues of confidentiality and privacy as primary ethical concerns, the principle of ‘no stigmatization’ became the key to ensuring this project did not violate other issues of no harm, confidentiality, privacy and more. As a result, the project produced an analytical model with insights into individual and contextual factors that may hinder or enhance reporting and registering domestic violence incidents. These insights in three countries also led the project to outline policy recommendations to improve the quality of gender data. Reports on this project will be published later this year.

A ‘North Star’ in project design and implementation

CODEs can serve as North Stars and sounding boards. Their members apply a fresh set of eyes to a project’s design, development and implementation and periodically demand that the implementing team question their actions, decisions and findings. The best performance of a CODE relies on its members being independent with low stakes in project outcomes. As critical outside voices, they provide important feedback that enables the project to succeed. In sum, CODEs ensure that data in development projects adhere to ethical standards by fostering critical self-assessment and accountability through a participatory approach.

“The CODE concept and operations manifest the values of the UN in the digital age, building trust in data and partnerships.”

- Fouad Mrad, Senior Programme Manager United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia

Ivette Yanez is Project and Communications Manager and Emmanuel Letouzé is Director and Co-Founder of Data-Pop Alliance. Follow Ivette on Twitter at @ivetteyanez_ and Emmanuel at @ManuLetouze.