Illegal mining is undoubtedly one of the greatest poverty-driven activities with far-reaching consequences. The cost of illegal mining on the natural and social environment far exceeds its benefits. From the pollution of water resources to child labor, the negative impacts of mining seem endless. Over the years, a lot has been done to address illegal mining on all fronts. However, tracking illegal mining activities and the mining locations has proven difficult. This is because these activities are well hidden in forest areas and along water bodies away from authorities.

In Ghana, illegal gold mining is called ‘galamsey’; a household term for the activity which vaguely means to ‘gather and sell’. In the mineralized regions of the country, galamsey is a major source of livelihood and this is another reason why it has been difficult to deal with. As a researcher with a keen interest in illegal mining, my focus was to map mining-induced hazards in the Prestea Huni-Valley municipality in Ghana. Lack of relevant data is a researcher’s worst nightmare and I spent some weeks trying to amass the information I needed.

My search for this location data led me to a news article on how the National Aeronautics and Space Agency (NASA) was helping the Ghanaian government fight galamsey with satellite imagery. Reaching out to Brian Killough, PhD, of NASA, I was introduced to the Africa Regional Data Cube (ARDC), an initiative to provide much-needed data over the African continent using products from Earth observation systems and various algorithms. I was provided with scripts that allowed me to access satellite data over my study area, prepare and process it using vegetation indices combined with the Water Observation from Space (WOFS) algorithm. Galamsey as a mining activity begins with the removal of vegetation cover and the creation of water ponds that are used for processing ore. As such, the identification of areas that have experienced significant vegetation loss as well as significant water gain in mining areas strongly indicates the occurrence of galamsey.

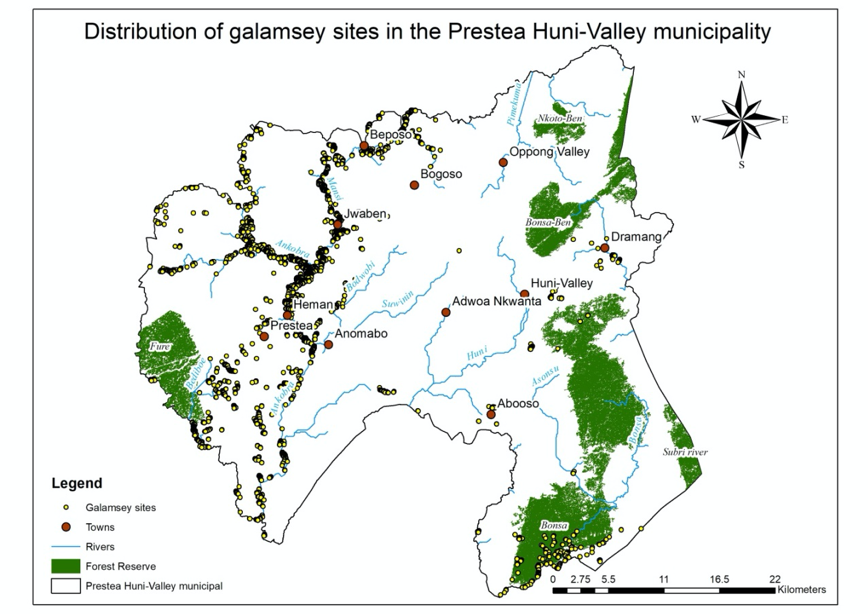

Using the ARDC’s resources, I identified as many as 3577 galamsey sites in the Prestea Huni-Valley municipality with data from January 2013 to January 2020. Many of these sites were in the municipality’s forest reserves and along its rivers like the Ankobra and Mansi rivers. These results formed the basis for my research as I combined it with other factors and methods to create mining hazard maps of the municipality.

In a time where there is a global call for sustainability, I believe the resources provided by the ARDC can be used to track galamsey daily. This will provide the local government and the forestry commission accurate information on the exact location of galamsey sites. Should these resources be employed, tracking galamsey will no longer be like taking a shot in the dark, but providing materials to contribute towards a well-coordinated and planned effort. This can translate into better decision and policy making where illegal mining is concerned.

As a student and a researcher, my experience with the ARDC partner organisations has introduced me to new ways of thinking. I was challenged in many ways to consider how technological resources, academic knowledge, and programming skills can be married to solve problems in our world today. While I had a little introduction to programming as a skill while working with the ARDC’s resources, my interest in the field has increased and invariably become a skill I hope to master in the future. Mining is but one environmental problem in a world where there are too many. I am encouraged and excited to find out how much of a difference we can make as people who care about the environment so that our future is better than our present.

Editor’s note: The Africa Regional Data Cube has been replaced by a continental scale data cube – ‘Digital Earth Africa’, for more information visit: https://www.data4sdgs.org/index.php/initiatives/digital-earth-africa