The COVID-19 pandemic has brought the need for reliable and timely mortality statistics into sharp focus. Knowing how many people are dying and where they are is essential to tracking the virus’ spread and virulence. While this sounds simple, COVID-19 has exposed deep and pervasive gaps in death registration systems in Asia and the Pacific, especially in low-income countries. Importantly, gender bias in death registration could be obscuring the pandemic’s gendered impacts.

We know that we are far from universal registration of deaths in Asia and the Pacific, and we know that COVID-19 affects men and women differently. But in many countries where few deaths are registered, men’s deaths are more likely to be counted. This means that estimates of COVID-19 death rates and excess mortality are underestimated and biased towards men.

Even without a pandemic, death registration is fundamental to measuring and mitigating critical health challenges. Ensuring women and girls’ deaths are registered, with cause of death recorded, is essential to understanding how sex can affect mortality, as well as the gender-specific burden of disease, such as maternal mortality.

Women and girls are less likely to be counted

Death registration tends to be lower when an individual has fewer resources, which is generally the case for women in China, India, and Morocco and Kuwait, among other countries. This means fewer incentives to register women’s deaths, for example, because there is less need for official documentation to resolve inheritance issues.

However, the extent of gender inequality in mortality statistics is hidden as there is insufficient information available on gender gaps in death registration. Especially for countries with lower registration completeness, it is hard to assess registration rates by sex. Sex-disaggregated death registration data availability is biased towards countries with better performing systems and higher registration completeness. Thus, we have little understanding of how COVID-19 differentially impacts men and women living with deficient death registration systems – usually in poorer countries, already more vulnerable to adverse outcomes. Even when death registration is nearly universal or national gender disparities appear low, there may remain significant gaps in certain settings or groups, highlighting the need for truly universal death registration.

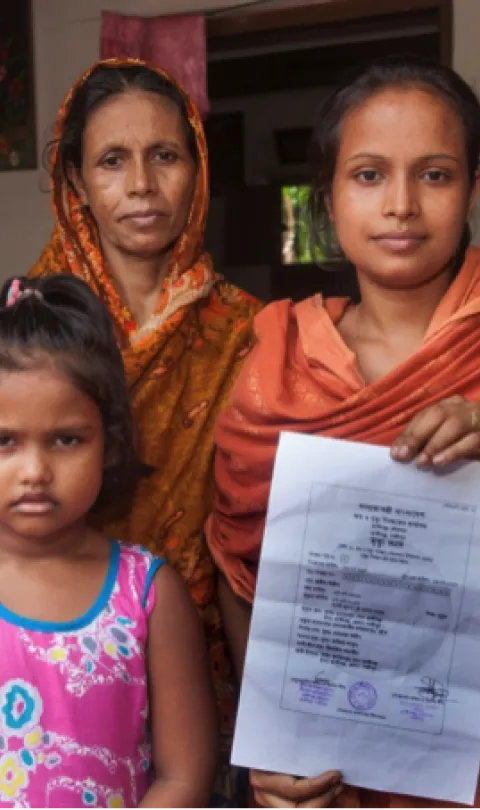

Weak death registration systems have broad implications for women. Since wives are more likely to survive husbands due to lower mortality and age differentials in marriage, and resources are often in men’s names, unregistered deaths can prevent women from accessing inheritance, living independently or remarrying. Without death certificates, it is almost impossible for widowed women to get pensions or bank accounts or transfer their husbands’ property rights to their names. This discrimination cannot be seen in the sex disparities in registration alone and requires qualitative research to uncover.

The road is long but progress is being made

The task of accurately registering deaths and recording causes of death is challenging in many poorer countries, especially since many deaths occur outside of medical facilities or without medical attention at the time of death. This means we know the least about people living in the poorest countries with the greatest burden of disease. We know even less about the situation of women and girls in these countries. As COVID-19 continues to spread throughout developing regions, the gaps in death registration systems are becoming more problematic.

We know we are far from achieving universal registration, and we know women are disproportionally affected when deaths aren’t registered. Now we need further analysis, with more disaggregated statistics, to obtain a clearer picture of who is left behind. We are letting women down by not registering their deaths – a devastating failure amid a pandemic, but we do not even know the extent, an even more profound failure.

In recognition of the importance of Civil Registration and Vital Statistics (CRVS) systems, governments in Asia and the Pacific undertook a Ministerial Declaration to "Get Every One in the Picture." In the declaration, countries in Asia and the Pacific commit to ensuring everyone in the region will benefit from universal and responsive CRVS systems that facilitate the realization of their rights and support good governance, health, and development. “Get Every One in the Picture” aims to improve CRVS systems in the region by forging political commitment, regional cooperation and accountability; facilitating knowledge exchange and technical assistance, raising awareness and encouraging innovation; and making tools and resources available. Accordingly, participating governments developed the Regional Action Framework on CRVS in Asia and the Pacific, which includes goals on universal death registration and the production and dissemination of accurate, complete and timely statistics (including on causes of death). There is good progress, but accelerated action is needed to achieve universal death registration in the region.

The COVID-19 crisis has intensified the need for well-functioning CRVS systems and highlighted the current shortfalls. Some countries have improved their systems in response. For example, New Zealand increased the frequency of reporting on mortality statistics from quarterly to weekly and Bangladesh is trialing the use of rapid mortality surveillance systems. To urgently address gaps in CRVS systems, countries may choose to implement alternative, possibly short-term measures to get the basic information needed to battle the pandemic. But unless the underlying systemic shortcomings are sustainably addressed, we cannot truly become prepared for similar challenges in the future.

If you are interested in knowing more about death registration and the impact of COVID-19, a session of the Asia-Pacific Stats Café series dedicated to the topic will be held on Thursday 23 July 2020 from 12:00-13:00 p.m. (Bangkok Time). More information is available here.