This report is the output of a workshop that was jointly hosted by the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data and Space4Climate.

Abstract

Data and technology can power climate action, from targeting investments in renewable energy to predicting and managing crisis events like floods and droughts. However, data and technology can also worsen the lives of those most affected by climate change with breaches of privacy, ethical dilemmas, and policy decisions with negative consequences for years to come. This report is the result of a workshop bringing together a diverse set of stakeholders to determine how ethical barriers can be overcome for inclusive and sustainable data-based climate action.

Introduction

For many communities around the world, floods and droughts pose major threats that are only exacerbated by climate change. They have devastating consequences for food security, property damage, and livelihoods. The power of data and technology in helping to forecast and manage these disasters cannot be understated.

Imagine a hypothetical scenario. You have been tasked with building a program to help the government of a low-income country in Asia. The government is looking to set up a data-driven early warning system for floods to better invest in protection and effectively respond to disasters. There is so much potential to put data to work: NASA has just built a portal to access free, real-time data on storms and flooding.

You decide to visit the areas being flooded to ensure your early warning system is working properly, asking the local affected communities about recent flooding events. However, they are reluctant to engage and share information. In fact, they hesitate––in the past, people that they know were evicted from homes in flood-prone areas. The locals do not want to lose their homes and have their data used against them.

With more time, effort, and resources, you gain the trust of this community. They tell you that the flooding is correlated with garbage blocking drains in the street. Your project becomes bigger in scope to also examine drainage and waste systems. The communities use the data collected as evidence in influencing the government to address the waste and drainage issues. Their streets become cleaner and the flooding is more manageable. The people who were most affected by the flooding used evidence and local action to tackle related issues and to mitigate the devastating effects of climate change.

These outcomes––community trust, evidence-based advocacy, sustained change––are major milestones of your program.

Unfortunately, a success story like this is not always the case in programs that harness the power of data and technology to combat climate change. In some cases, data and technology have more power to do harm than good, particularly as the pace of technological change outstrips our collective ability to reflect on what we are doing and why. The data and technology meant to help affected communities can result in breaches of privacy, ethical dilemmas, and policy decisions with negative consequences for years to come.

These are the issues that we explored at our Climate Partnerships Learning Session on June 29th, 2021, jointly hosted by the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data and Space4Climate. The workshop brought together people with wide-ranging experiences, united by an interest in data-based climate action. The group included designers of data solutions, people working with local communities, and professional accreditation bodies for climate scientists. There were more than 40 participants representing 34 different affiliations from 16 countries across Africa, Europe, and Asia-Pacific. This report explores the findings and outcomes of the session.

Perspectives on climate data ethics

To frame the discussion, participants were asked about their perspectives on the ethical credentials of the climate data field.

At the start of the session, nearly nine in 10 agreed that the field could benefit from improved ethical consideration. Interestingly, participants were neutral when asked whether the climate data field is ethical as it stands today, but felt that unethical practices would become a larger issue in the future.

By the end of the session, participants were more likely to recognize that there are ethical issues in the field as it stands today, and half thought that unethical practices were already occurring. The proportion who believed that ethics will become a larger issue in the future grew from six to eight in 10, while the benefits of improved ethical consideration were unwavering.

Click the arrow to explore the full visualization.

The challenges around driving inclusive, data-based climate action

Despite the potential of data and technology to drive climate action, there are numerous pitfalls relating to power imbalances and political will, data gaps, and the challenges in bringing together the right expertise to drive sustainable solutions. In the scenario outlined earlier, you may not have had the time or money to consult local communities. You may have built a data system that was not useful, or worse, built a system that resulted in people losing their homes. Perhaps there was not enough commercial or financial support for the NASA data products you were using, and there was no more real-time data for the flood warning system.

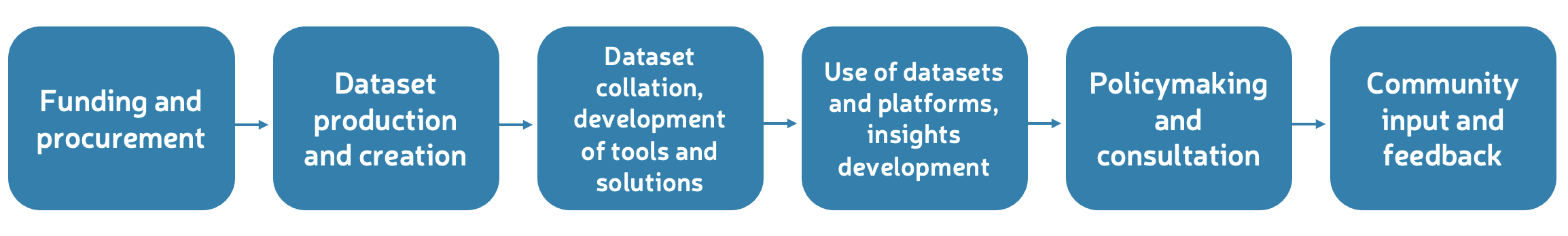

To think through where obstacles may arise, the session presented data-driven climate action as a chain of processes and stakeholders, from funding and procurement to community impact and feedback. Interestingly, there was much debate about whether the system is circular with healthy feedback loops or more linear, reinforcing inherent power structures.

When asked where the weakest links are in inclusive, evidence-based climate action, the collective view was that the links at opposite ends were the weakest: funding and procurement, along with community input and feedback. Given the weaknesses and disconnectedness of these links, data-based climate action is likely to be a linear process as it stands today, reinforcing power imbalances.

There was consensus that change needs to happen at the funding stage. Currently, contractual requirements are very strict and rigid and there is limited flexibility and lacking emphasis on the multi-stakeholder collaboration needed to successfully deliver programs. One participant asked: Why should we have to detail the return on investment of things that keep us alive, like biodiversity? Can you put a price on cross-species solidarity?

“The pushback we’re getting on [fundraising for a biodiversity program] is the return on investment. It’s really hard to measure it... and should we even have to measure the return on investment of natural capital, things that help us stay alive and help the planet thrive?” –Participant, multilateral

At the other end of the chain, engaging communities is a resource-intensive and complex task. No organization can engage with every community and user group in all corners of the world. Better mechanisms for community engagement and better use of partnerships that can integrate the views of local communities in all stages of evidence-based climate action are necessary. A framework for inclusivity and co-creation could help with designing programs that are continuously responsive to the needs of users and local communities, and therefore more likely to see continued uptake after initial funding ends.

“Partnerships play a huge role because there does need to be coordination. Climate impacts don’t respect sectoral or geographic boundaries. People need to be working together, making sure that we’re being inclusive–partnerships can help to identify and reach out to the people who need to be involved in decision-making.” –Participant, government

The chain links in the middle fared better. Data production was deemed the strongest link––there is certainly a lot of useful data in the world that can be harnessed for climate action. There is also no shortage of tools and solutions. In fact, a consistent reflection was that there are too many tools and solutions and much confusion among all stakeholders about their differences and similarities.

A lot of resources (and emissions) are wasted in processing the same data and building the same solutions without adequate use and uptake. The focus should be on what already exists rather than investing in duplicative efforts and shiny platforms. Otherwise, our efforts risk ending up, as one participant put it, in the “platforms graveyard” as priorities change and seed funding ends.

“Many dashboards seem nice, but do they take into account long-term needs? Recently elected governments want to do ‘hot things’... but then the government changes and all the platforms become a graveyard.” –Participant, academia

Hover over the visualization (or click on a mobile device) to see what weaknesses workshop participants identified. Click the arrow to explore the full visualization.

The essentials of inclusive, data-based climate action

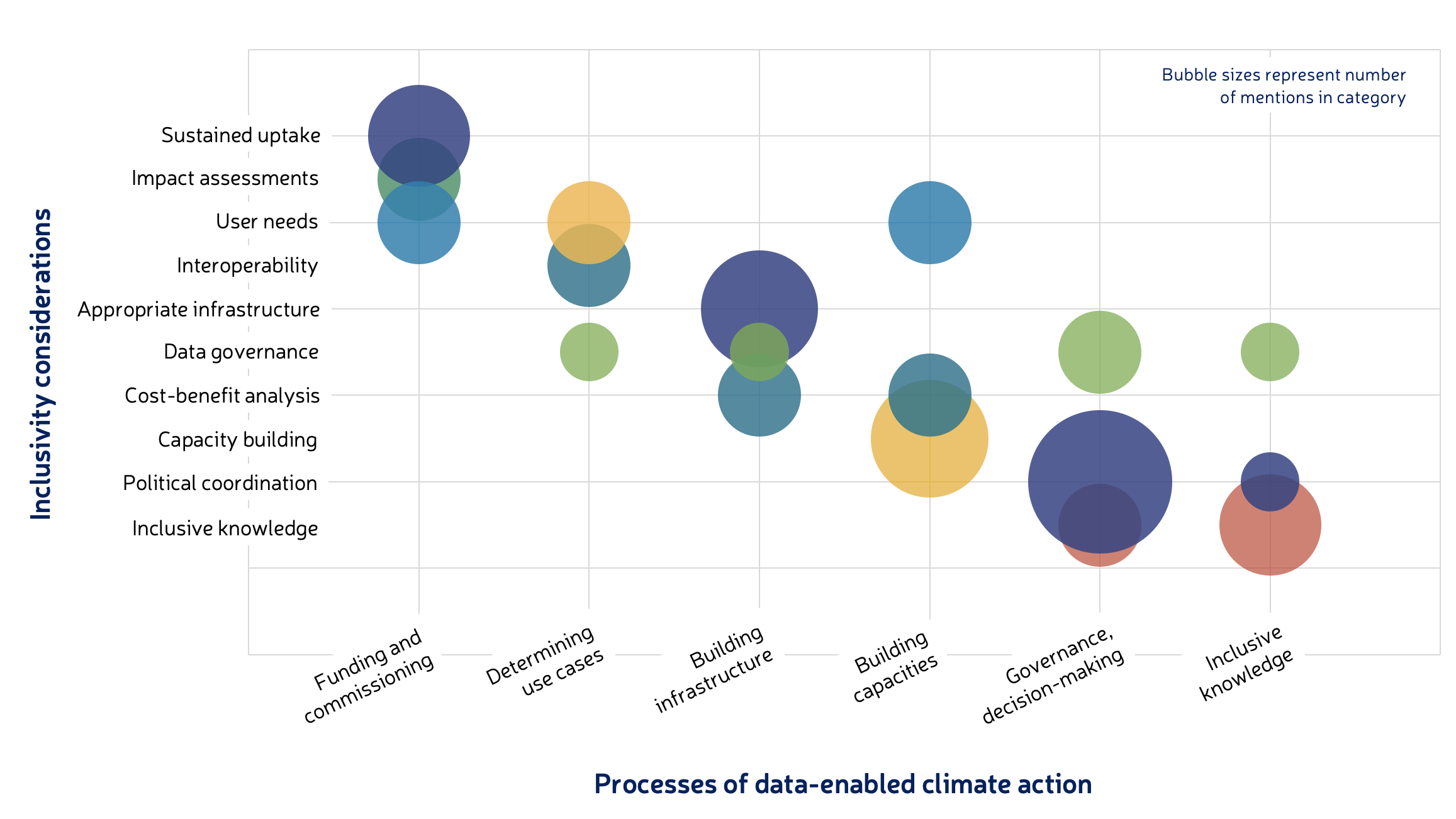

Participants were asked to reflect on what an inclusive data system for climate action means. Key questions included: What must we consider to ensure climate data programs are appropriate and do more good than harm? How do we deploy inclusive, evidence-based climate action?

Designing solutions that are inclusive and fit for purpose must begin with funding and commissioning and include feedback mechanisms at every stage of the process. Ultimately, designing solutions that maximize user uptake and have a lasting positive impact on affected communities increases the chances that they will be sustained after initial funding ends.

There are multiple inclusivity considerations at every stage of data for climate action programs, from ensuring that solutions cater to internet bandwidth among users, to not privileging technical skills over knowledge about local ecosystems and communities. The fundamentals of inclusive, evidence-based climate action were mapped out by participants in the learning session.

Hover over the visualization (or click on a mobile device) to see all of the essentials of inclusive, data-based climate action identified by participants.

There are different things to consider with each process and stage of data-enabled climate action. At the funding stage, assessing whether the solution is truly needed and fit for purpose is critical. Sustainability plans should accompany any funding, and the implementing teams should be diverse to solve complex problems.

User needs have to continuously be evaluated as systems for data-based climate action are built and improved––user needs change and certain issues become more urgent. The systems built need to be interoperable, so that, for instance, data can be used not only to respond to disasters, but forecast them too. The systems have to be cost-effective, and decision-makers should be supported in building the business case for investing in the solutions that help them combat the devastating impacts of climate change. Institutional memory can’t be forgotten: when people leave, knowledge leaves, and sustained knowledge transfer is key.

Data governance is as much of a socio-political issue as it is a technical one. Who decides what data is collected and for what purposes? How can we increase participation and shared decision making?

“Citizens’ Assemblies, as a way of increasing feedback from a broad cross-section of stakeholders and developing ‘buy-in’ for climate initiatives, is worth examining more frequently… It’s quite easy for the loudest voices to dominate in engagement, whereas Citizens’ Assemblies aim to find representatives from a wide cross-section of people.” –Participant, private sector

The importance of robust political coordination and meaningful community engagement cannot be understated. Effective climate action must build on a common understanding of existing challenges faced by different stakeholders. To understand the whole picture, trust between stakeholders is critical. This means not privileging certain kinds of knowledge above others and not elevating technical skills over local knowledge.

“[There are] inherent power imbalances–who decides what data is collected and for what purposes? How can we increase participation and shared decision-making?” –Participant, non-profit

Four ways to build inclusivity into data-based climate action

Perhaps no one can address every inclusivity consideration, but everyone can do something.

Here are the four must-do’s of responsible and sustainable climate data programs that were prioritized:

- Engage local communities before the program scope is finalized to make sure the data is useful, and the program considers local needs––create opportunities for communities to define their own challenges and priorities.

- Create a diverse committee of stakeholders (including stakeholders with local, Indigenous knowledge) and a committee of multi-disciplinary scientific advisors (including social scientists) to guide program development, maintaining a balance between technical and local knowledge.

- Actively and meaningfully engage civil society and non-governmental organizations––this is crucial, as these groups can drive sustainability and a sustained uptake of tools and solutions when governments change.

- When looking at creating tools, do not reinvent the wheel. Focus on what works, what is likely to be maintained in the future, and how new programs can sustain existing tools.

Appendix 1: Participant information

Appendix 2: Workshop format

In preparation for the workshop, eight key informant interviews were held to guide the structure of the session, discussion, and co-creation exercises. The key informants were affiliated with the following organizations:

- Food and Agriculture Organization

- GIZ (German Corporation for International Cooperation GmbH)

- Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data

- Group on Earth Observations Indigenous Alliance

- Humanitarian OpenStreetMap

- London Climate Change Partnership

- Royal Meteorological Society

- UN Environment Programme - Danish Hydraulic Institute

Along with diverse speakers and participants, this research-driven approach created a robust framework to assess ethical issues in data-based climate action. The questions posed to the participants are as follows:

- What does an inclusive data system for climate action mean to you?

- Have you encountered ethical dilemmas in data-driven climate, environment, and disaster management?

- Have you seen ethics play a bigger role in data-driven climate, environment, and disaster management? Are we moving towards professional accreditation for data ethics and stewardship?

- Have you ever faced a situation where not including some stakeholders had a negative impact on a data program or data-driven decision making?

- Where do you think the weakest link is in the value chain of data systems for climate action? How can it be fixed? Are there good examples of where this works?

- How can policy making be strengthened to include more relevant information and points of view? What activities can partnership brokers introduce to support policy makers?

- What role does Indigenous and local knowledge play in evidence-based decision making for climate action?

- What are the key things a partnership broker must consider to ensure that data partnerships are inclusive and fit for purpose?

- How can data systems be designed for continued uptake and use without additional funding? How can data systems that are discontinued be resurrected?

- If your organization were asked to enter a data partnership (eg, by sharing data, conducting training, data-driven policy making, providing community feedback, etc), what would be some of the organizational barriers and incentives for collaboration?

This event took place online with panel discussions and a series of interactive co-creation exercises. The full details of the session can be found this briefing pack.This format enabled live participation from Africa, Europe and Asia-Pacific.

Appendix 3: Further reading

The Brokering Guidebook, the Partnering Initiative

The CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance, various stakeholders

Data Ethics Canvas, Open Data Institute

FAIR Principles, GO FAIR Initiative

Lessons Learned Report: Advancing Inclusive SDG Data Partnerships, the Danish Institute for Human Rights, International Civil Society Center, Partners for Review

The Power of Partnership, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank

Principles for Data Partnerships, Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data

Written statement, Group on Earth Observations

Written statement, Open Development Cambodia

Appendix 4

The outputs from the Mural co-creation exercises can be for here: