A note on our audience

This paper outlines the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data’s (Global Partnership's) thinking on accountable data governance based on engagement with our network of more than 700 partners from academia, the public sector, the private sector, nonprofit organizations, and multilateral organizations from all over the world. It includes practical reflections of use to practitioners and decision-makers interested in developing new and better approaches for governing data to benefit people.

Acknowledgements

This paper draws on the experience of the Global Partnership’s Secretariat team and broader network of organizations, to which we are greatly indebted. The contributions of Karen Bett, James Henderson, and Fredy Rodriguez Galvis were invaluable, and the authors extend appreciation to them for providing guidance and sharing examples from their work. Thanks are also due to Jenna Slotin, Claire Melamed, Lizzy Hvide, and Jennifer Oldfield for their thoughtful comments and suggestions.

I. Understanding the data governance landscape

Data governance is a hot topic across the public and private sectors. Discussions around how to govern data are increasingly common and urgent among organizations working to leverage data and technology to advance sustainable development. This is due at least in part to a number of high-profile scandals in recent years related to misuse of data and the illegal (or unethical) sharing of data by both private- and public-sector players.

Yet, despite this, the meaning of “data governance” remains unclear. In the absence of a formally and widely agreed upon definition, data governance means different things to different people. The term emerged from private-sector practices for managing data, but in the last decade it has evolved to encompass laws, policies, strategies, and decision-making in the management and use of data by a single organization or multiple parties. In 2021, the World Bank characterized data governance as “the tangible expression of a country’s social contract around data.” The term applies to a wide range of activities, from how small organizations use data on a daily basis to how international agreements treat data privacy and sharing. It also refers to how decisions are made and how organizations interact in the context of bilateral or multilateral data sharing, such as through data collaboratives or shared data platforms.

Based on what these definitions and perspectives have in common, we describe data governance as decision-making related to data with outcomes that impact the entire data value chain and the people involved in and/or affected by data use. At the Global Partnership, we have adopted this broad definition of data governance because we understand that decisions about data affecting individuals and communities can be made at different stages, e.g., when the data is collected or when it is shared with others. We recognize that these decisions take different forms, including legislation, international treaties, and internal organizational policies, and we believe it is pivotal to focus on decision-making processes to understand who makes these decisions and in what ways.

Connecting data governance to digital development that works for everyone

In 2022, the United Nations (UN) Secretary-General called on all countries to establish a Global Digital Compact to promote an “open, free, inclusive, and secure digital future for all,” to be agreed upon in 2024. This is a goal that everyone should support, as the Global Partnership’s Senior Director of Policy, Jenna Slotin, argues: “Making digital economies work for everyone is a complex challenge rooted in how the data that is produced and used by these systems is managed and governed.”

Countries’ digital and data agendas are closely intertwined. Digital tools and systems run on data that allow organizations to deliver personalized services to citizens where and when they are most needed, and data analysis leads to insights that inform policy choices. This is why, Slotin writes, “the greatest potential for improved service delivery and decision-making comes from linking and mining these databases.”

However, as many (including the UN) have acknowledged, these practices threaten privacy and human rights. Vast amounts of data can be a goldmine for organizations willing to deploy surveillance practices and can be vulnerable to data breaches and misuse even when managed by well-intentioned stakeholders. Consequently, data governance and management is at the heart of the success or failure of an open, free, inclusive, and secure digital future for all.

Read Jenna Slotin’s blog "In digital transformation, the devil is in the data."

Global Digital Compact consultation hosted by ITU in Bucharest, Romania. Credit: ITU.

We are not alone in adopting a definition of data governance focused on decisions rather than specific types of outcomes. It’s increasingly common to view data governance as concerned primarily with decision-making processes around how data is stored, managed, publicized, shared, used, and reused. And there’s broad agreement among organizations focused on using data for social good that people and communities should be part of decision-making processes around data that affects them. But these conversations typically go no further than affirming that opening up processes to encourage transparency and participation is important.

Stopping there, however, does not help us to address the key challenges related to data and power, notably concerning (a) the concentration of power in decision-making around data even as the people who have the most to gain or lose from these decisions are largely excluded from the process of making them, and (b) the lack of practical recommendations and examples for people trying to make data decisions more transparent and accountable.

At the Global Partnership, we work with our diverse network of more than 700 partners to build the data systems they need to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. This work translates into a significant focus on the data itself—ensuring that it is timely, reliable, accurate, and inclusive, representing the diverse needs and experiences of all people and communities. It also requires that the institutions and decision-making processes around data are accountable to the people from whom the data originates and to the people and communities affected by its use. Based on broad consultation and learning across our network, this paper aims to shed light on ways to make data governance more accountable, and to lay out practical steps to achieve this.

What is accountable data governance, and why does it matter?

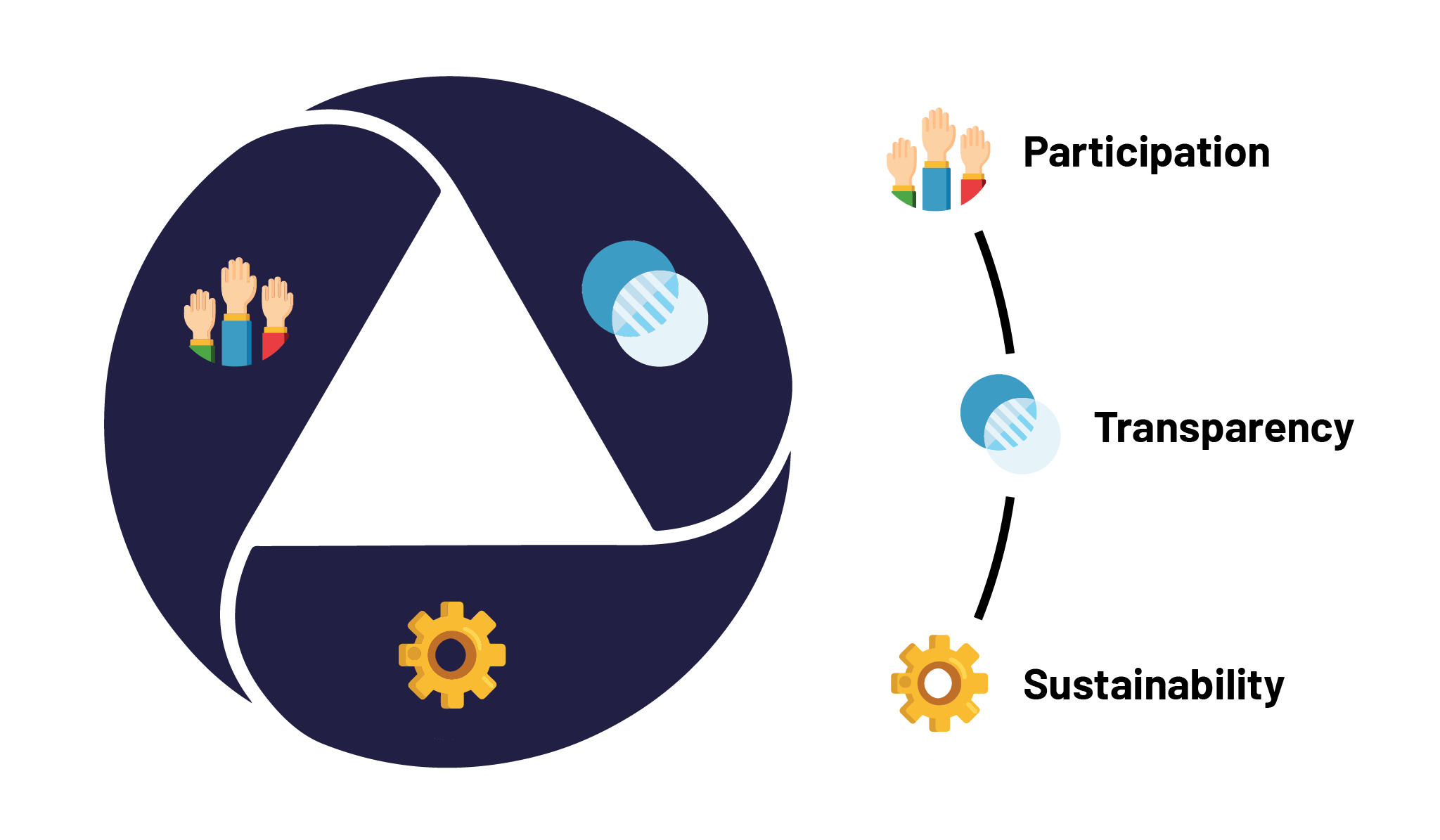

Accountable data governance refers to decision-making strategies, policies, and practices characterized by participation, transparency, and sustainability. In this context, participation means that mechanisms for individuals and communities to take part in decision-making are available and accessible. Transparency means that decision-making processes are visible and understandable and that decision-making powers and rules are clear and explicit to all stakeholders, especially people and communities impacted by data decisions. Finally, sustainability refers to the reality that mechanisms for ensuring transparency and citizens’ participation are not one-offs. Rather, they must be embedded in data governance practices and be consistently replicated and implemented over time. They should be integral parts of data governance approaches instead of occasional tokens.

Implementing accountable data governance is a precondition for buildingtrust among stakeholders in how data is collected, managed, and used. If the management of data by organizations—whether governments, companies, civil society organizations, or multilateral bodies—is not trusted, their use of data cannot be sustained over time, as people will stop supporting these institutions’ use of data. For instance, when WhatsApp updated its terms of service in 2021, users’ lack of trust in the new rules led millions to immediately switch to rival company Signal.

Also in 2021, the UK government came under legal scrutiny for its contract to provide data from the National Health System (NHS) to data analytics company Palantir. The former Deputy Chair of the British Medical Association, Kailash Chand, described the impact: “The secrecy around what the government is doing with NHS data, working with companies like Palantir, will damage what trust is left amongst ethnic communities, for migrants, and in the NHS family as a whole. It makes it difficult for people like me to convince ethnic minority people that this is being done in their best interests.” Indeed, refusing to provide data or participate in data collection is one way to protest opaque processes or misuse of data by institutions, especially among communities that have historically been marginalized.

In contrast, when people have a say in how their data is used, more trusted and trustworthy data systems lead to more equitable and effective data use and reuse. Accountable data governance paves the way for fair and sustainable data ecosystems.

Reflecting lessons from our network

The Global Partnership is uniquely positioned to contribute to making the conversation on data governance more practical by advocating for greater accountability in decision-making processes and by suggesting practical steps to achieve this. We can share knowledge and experience on accountable data governance strategies from our network of partner organizations, representing governments, donors, civil society organizations, companies, academic institutions, and nongovernmental and multilateral organizations.

Since the Global Partnership’s founding in 2015, its mission has been to create connections and spaces for people and organizations to share knowledge and collaborate to leverage the power of data to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. In early 2021, we led the formation of the Data Values Project, a global policy consultation and campaign focused on developing principles to underpin a fair data future. During a year-long consultation, we received contributions from more than 350 individuals from 63 countries and from a broad range of sectors, communities, and regions. The results of this consultation led to the publication of a white paper, “Reimagining data and power: A roadmap for putting values at the heart of data,” and the launch of the #DataValues Manifesto in 2022, which calls on governments, companies, civil society organizations, donors, and others to shift power in how data is funded, designed, managed, and used.

This paper reflects the outcomes of these consultations and learnings from the Data Values campaign along with lessons from nearly a decade of establishing multi-stakeholder, participatory fora and assisting governments and organizations in increasing their knowledge of data governance. It promotes practical steps by focusing on (a) recommendations for creating spaces for participation and inclusion in data governance and (b) strategies for building capacity to encourage leaders to adopt accountable data governance practices.

II. Building trustworthy data systems with participation at their core

Meeting public demand to participate in data governance

A strong relationship exists between the existence of spaces for participation and stakeholder involvement and trust in data collection, management, and use. As the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted, organizations and governments in particular cannot rely solely on their existing credibility capital to be considered trustworthy by individuals and communities concerning their use of data. This was exemplified by the adverse response to contact tracking apps in European countries that are generally characterized by strong trust in institutions, such as Norway, where the country’s Institute for Public Health was forced to withdraw its original COVID-tracking app amid growing backlash from Norwegian media and society concerning the possibility of continuous location tracking of users.

Creating and maintaining dedicated spaces for participation in deliberation around data collection, sharing, and use is essential, and demand for such spaces is rising. The appeal of transparent decision-making emerges clearly from the input received during the Data Values consultation and the burgeoning literature around data trusts, data cooperatives, citizens data assemblies, and other forms of participatory data governance. Experimental initiatives such as Understanding Patient Data from the Wellcome Trust, which aims to foster transparency, accountability, and public involvement in the way patients’ data is used in the UK, and Ictio (part of the Citizen Science for the Amazon project), which collectively developed a fishing management app and data use policy with communities in the Amazon basin, demonstrate demand for increased participation.

An example from Ghana illustrates the impact of establishing such spaces at the national level. Ghana is one of the few countries in the world where the national statistical office has access to data from mobile network operators (in this case, Vodafone Ghana) on a long-term basis and which has received no major backlash from individuals or civil society for this partnership. The story is different in Kenya, where initial attempts by the country’s Communications Authority to access data were discontinued after they were challenged in court. This difference is due at least in part to the collaborative approach to transparency and accountability taken by the Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) and its partners. When the COVID-19 pandemic struck and access to data became more relevant for all government services, the partners set up a steering committee to consider requests for data access from parties other than those in the agreement (GSS, Vodafone Ghana, Vodafone Foundation, and Flowminder). This steering committee, which has since become a permanent feature of the project, includes representatives from civil society organizations that work to protect digital rights. Their participation ensures that groups that bring a digital rights perspective can weigh in on ethical considerations in such decisions and can hold government and private actors accountable through the decision-making process.

Even when the demand is not clearly articulated, creating spaces for participation in data governance can be surprisingly effective in mobilizing individuals and communities that were not previously involved. This emerges very clearly from national-level experiences. In Senegal, for example, data users long questioned the trustworthiness of the annual agricultural statistics produced by the Ministry of Agriculture. This led to a proliferation of alternative statistics and duplication of efforts. In early 2022, IPAR (Initiative Prospective Agricole et Rurale), a regional think tank, and Senegal’s National Statistical Agency launched the AgriData Platform with support from Development Gateway. This multi-stakeholder forum was set up to align interests and resolve conflicts around data production. More than 50 stakeholders from government, civil society, and academia participated in this work over the course of one year. When an opportunity to participate arose, interested parties rushed to be involved and proved to be more than willing to contribute to better data management.

Understanding participation in the context of data governance research

The increase in discussions around data governance in recent years is reflected in work by numerous research institutions—among them the Ada Lovelace Institute, the Open Data Institute, and the Aapti Institute—that are developing thinking and testing approaches for increasing accountability in the way data is collected, managed, and used.

The Open Data Institute has led the reflection on data institutions to illuminate their capacity to steward data on behalf of citizens and communities. The Datasphere Initiative has published a Governance Atlas, which maps organizations in the data governance ecosystem, and is currently supporting experimentation with sandboxes for enabling accountable data sharing across jurisdictions. The Centre for Global Development has contributed research linking data protection laws and data governance and detailing the role that multilateral organizations have to play in strengthening global data governance practices. The GovLab has focused on developing the concept of data stewards, who “are organizational leaders or teams empowered to create public value by re-using their organization’s data (and data expertise); identifying opportunities for productive cross-sector collaboration[;] and responding proactively to external requests for functional access to data, insights or expertise.” The Ada Lovelace Institute has also contributed to the conceptualization of data stewardship from a legal perspective and by analyzing legal mechanisms to put data stewardship in place.

In comparison, less attention has been paid to how to encourage and enable ongoing participation from stakeholders, including building data governance–related skills and competencies. Notable advances have been made by the Open Data Institute through its work on data institutions, the Aapti Institute and Data2X in their work on data cooperatives, and the Ada Lovelace Institute in its work on participatory data stewardship. However, promoting accountability through greater participation in data governance remains relatively under-explored.

When it comes to participatory mechanisms, the level of investment required to take part (from simple consultation to collective decision-making) and the format (from data trusts to steering committees) can vary, but all rely on the assumption that individuals and communities are entitled to shape, directly or indirectly, the decisions about data that affect them. This acknowledges that certain forms of participatory data governance (i.e., those involving direct representation) require higher levels of engagement, knowledge, and skills than others (for instance, those involving delegation), and can therefore be more burdensome for participating individuals and communities.

A tech consultant from India speaks at a meeting. Credit: Wonderlane.

Data stewards can facilitate greater participation

Data stewardship has emerged as a function or role to facilitate the trustworthy and responsible management and use of data. While the precise understanding of data stewardship is still a matter of debate, it is clear that data stewards can play a central role in creating multi-stakeholder partnerships, facilitating the participation of new actors, and engaging communities in data access, sharing, and use. Data stewards can open up data governance processes to broader consultation, scrutiny, and collective decision-making. Given the impracticality of including everyone in decision-making processes, they can also contribute to finding the right balance between delegation of decision-making powers and the establishment of participatory multi-stakeholder processes.

People who fulfill these functions and possess the relevant skills are still scarce in most countries. A recent study from the Centre for the Study of Economies of Africa on responsible data governance in Africa analyzed this skills gap across Nigeria, Morocco, Kenya, Mauritius, and South Africa and suggested that, in these countries, “both private and public data-driven entities that should apply data governance principles to their processing workflows are yet to establish data governance roles within their organizations.”

Creating spaces for participation and rooting data stewardship functions within organizations are pivotal for achieving accountable data governance.

III. Strengthening leaders’ capacity to adopt accountable data governance practices

Historically, successful data governance has been equated with adopting policies and strategies and creating secure infrastructure for data management. As in the context of discussions around data interoperability, the bulk of the attention has been trained on the technical aspects of governance (such as processes and infrastructure) rather than on people. This focus ignores the fact that the success of such mechanisms depends on the people who oversee and implement data management practices and governance policies.

Our experience working with governments and nongovernmental partners suggests that data governance skills have been consistently overlooked in data-related investments. These skills include a wide range of competencies related to data management, data ethics, legal aspects of data sharing (e.g., liability, intellectual property, and privacy), stakeholder engagement, fostering participation, and negotiation and communication skills.

Beyond compliance: Why data governance skills matter

Despite clear evidence of their importance, building people’s skills and knowledge is rarely at the forefront of discussions around data governance. Most discussions around data skills focus on increasing technical capacity and training data scientists or, alternatively, on improving general data literacy among individuals.

Increasing technical skills and data literacy are important to bring about a fair data future, as the Data Values white paper “Reimagining Data and Power” highlights. However, increased technical skills and widespread data literacy are not sufficient on their own to achieve accountable data governance.

When data governance skills are lacking and decision-makers do not understand the importance of governing data responsibly or of building and maintaining trust, data governance decisions are confined to compliance with existing laws. When data governance skills and knowledge are weak or absent, as is still the case in around 25 percent of countries, accountability is also weak or absent.

There is mounting evidence that weak data governance creates opportunities for exploitation. For instance, recent literature on data colonialism explores how organizations based in the Global North have been able to implement extractive data practices in Global South countries due to their perceived or real weakness of the legal frameworks. The Free Basics limited internet service that Meta (formerly Facebook) provides in developing markets, for instance, has been accused of harvesting huge amounts of metadata from its users and violating net neutrality rules, according to an investigation conducted by Global Voices in Colombia, Ghana, Kenya, Mexico, Pakistan, and the Philippines.

China’s digital colonialism, which South African scholar Willem Gravett has defined as activities advocating for internet sovereignty (versus a global internet approach), is another prime example. Gravett argues that China encourages African governments to implement censorship in order to export authoritarian surveillance technologies and deploy AI and data mining techniques across the continent. This has been made possible by weak privacy and data protection legislation as well as lack of direct knowledge and experience of decision-makers, according to research by the Insikt Group.

As these researchers suggest, when data governance skills are lacking both among decision-makers and within the broader public, the only bulwark against misuse of data by governmental and nongovernmental organizations is laws and policies. Compliance with laws when they exist is important but does not meet the high standard of accountable data governance. And, when the necessary laws and policies are weak or absent, a lack of data governance skills prevents opportunities for checks and balances through participation to emerge.

Protect Net Neutrality rally in San Francisco, 2017. Credit: Credo Action.

Given the wide range of skills and contexts for data governance, related competencies are not easily taught and are often left out of data science and other technical programs. Discussions around data stewardship and the skill sets required of data stewards, at the organizational level and across sectors, are helping to shed light on this area.

Skilled and informed leaders and data stewards are necessary to establish data governance mechanisms that hold public and private organizations accountable to their citizens, customers, and partners. This requires decision-makers to understand the importance of data governance and to be confident creating mechanisms for participation and participatory decision-making.

In Colombia, for example, the management of the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE) has been particularly interested in data governance issues and has been willing to experiment with formal and informal participation mechanisms. This has been reflected in its work with communities at risk of marginalization, such as indigenous populations, LGBT communities, and racial or ethnic minorities. In recent years, DANE has worked to adopt consultative and collaborative approaches that allow communities to influence how data is collected, managed, and used. DANE's efforts to make data available on LGBTQ people included a participatory process to create a questionnaire for what would become the first national survey of the social status of people disaggregated by gender identity, sexual orientation (LGBTI) and other non-hegemonic sexual orientations and gender identities. This process generated conversation spaces to identify information needs, in which more than 50 people participated, including LGBTI organizations at the national and subnational levels, representatives of national and subnational institutions that develop public policy, and academic institutions. Increasing trust among collaborators has led DANE to become more open, transparent, and responsive to communities, resulting in more accountable data practices and better data.

Building communities of learning

Our experience at the Global Partnership confirms that the most effective way to grow decision-makers’ understanding, confidence, and soft skills around data governance is through direct experience (for instance, through peer learning) rather than through formal training. On-demand training is scarce (few if any training resources focus on the skills required for accountable data governance), and even fewer resources exist in languages other than English. Because many decisions around data governance are context specific, peer-to-peer learning offers decision makers opportunities to hear multiple perspectives and share best practices.

The power of peer learning and informal exchanges was one of the key findings of the Global Partnership’s project on unlocking privately held data for public good. In supporting Uruguay to lay the foundation for successful public-private data sharing, we found that facilitating formal and informal knowledge exchanges among countries and creating opportunities for peer learning was not only necessary (as off-the-shelf training on this particular topic was non-existent) but incredibly effective in building the confidence and skills of leaders within Uruguay’s National Statistical Institute (INE). Within two years, INE went from piloting new governance approaches to data sharing with the private sector to becoming a global thought leader in this domain.

Many policymakers are eager to share their challenges and learnings about data governance and to participate in discussions and exchanges around this topic when given the chance. The data for good community has an important role to play in filling the data governance skills gap by facilitating interactions and peer learning among countries and organizations. Initiatives such as the Data Stewards Network from the GovLab can help by “bringing together responsible data leaders from across corporations to share knowledge and jointly advance a new, more professionalized approach for data collaboration.”

IV. Mainstreaming accountable data governance

Despite the excellent work done by many organizations and the many pilot projects and initiatives that have emerged in the last few years, accountable data governance practices are still not widespread.

Focusing the discussion on participatory mechanisms and skills, however, can be a driver to test new approaches and solutions for achieving more accountable data governance. Multi-stakeholder partnerships, public consultations, steering and ethical committees, and peer-to-peer learning and exchanges are some of the instruments that already exist within the toolbox of many organizations and that do not require extensive legislative or regulatory power to put into action—just some goodwill, time, and resources.

In the coming months and years, the Global Partnership will focus on elevating accountable data governance by demonstrating to public, private, and nonprofit organizations that strategies and approaches exist and the skills can be developed to make data governance more participatory, transparent, and sustainable, even when the legislative environment is underdeveloped. We will particularly invest in filling the gap of data governance training and in bringing partners together to meet the increasing demand and needs of stakeholders and policymakers from all over the world seeking to embed accountable governance in their data systems.

Of course, we cannot do this on our own. Just as we have responded to members of our network who identified accountability as a linchpin of effective data governance, we call on partners to join us in this journey by participating in pilots, experiments, research, and knowledge-sharing activities around trustworthy participatory mechanisms for governing data. Together we can move the needle and contribute to developing fairer data systems for all.

We want to hear from you!

Is your organization experimenting with new models of data governance to include people in decision-making at the regional, national, or local level? Are you implementing innovative ways of ensuring people's voices are part of data decision-making?

The Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data wants to hear from you. Reach out to [email protected] to explore collaboration and to share resources, training, and more.