The power of data to promote sustainable and inclusive growth depends on the reliability of this data. And data produced by governments can only be as good as the statistics officials in government who are producing it.

Reflecting this, the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data’s strategy underscores the importance of skills and skill-building for good data. Yet, surprisingly little is known about the skillsets of those producing government data–that is, statistics officials in governments. Prior to our report, we did not have data about those producing sustainable development data and government statistics more generally. How competent are they at analyzing statistical data? How motivated are they to excel at data production? Do they uphold integrity when producing data, even in the face of opposing career incentives or political pressures? And what can be done to ensure those producing government data are competent, motivated, and ethical when doing so?

We surveyed 13,300 statistics officials in 14 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean to find out. Five results stand out. For further insights, consult our Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) report, Making National Statistical Offices Work Better.

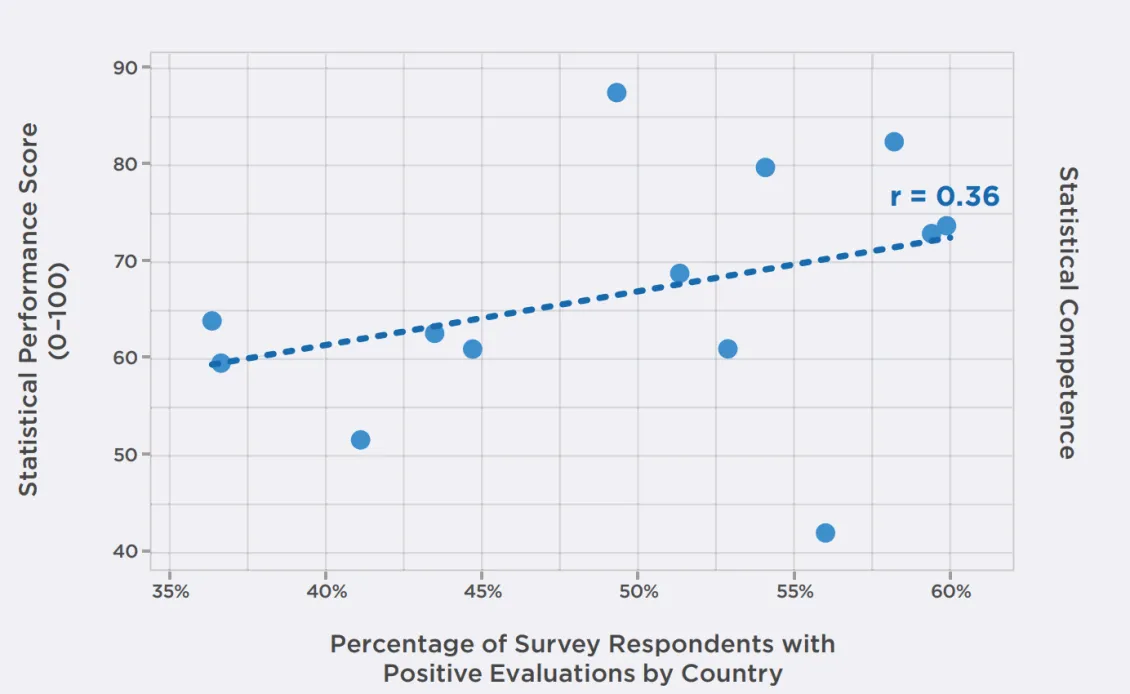

1.The quality of government data is associated with the competence of statistics officials.

The World Bank’s Statistical Performance Indicators measure the performance of a country’s statistical system. This performance correlates (r = 0.36) with how competent statistics officials are, according to our employee survey.

We measure that competence by including a short statistics exam in our survey, which assesses basic statistical competencies, such as descriptive statistics and probability.

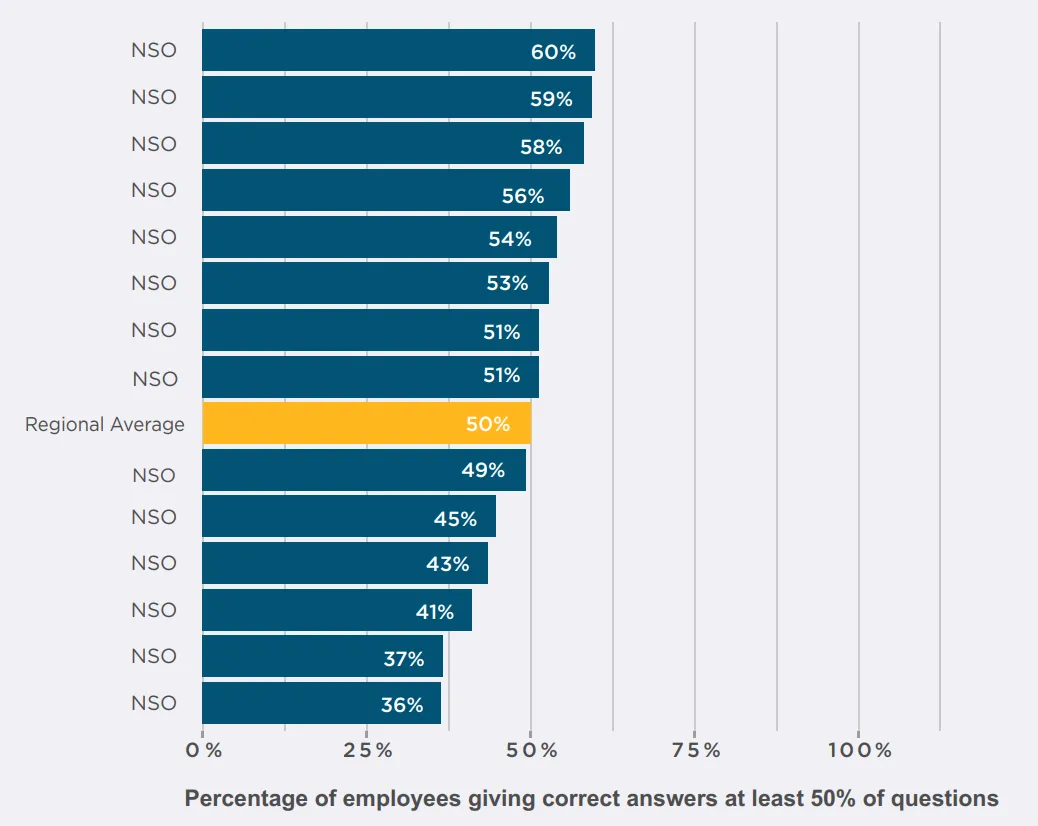

2. Many statistics officials lack fundamental statistical competencies, highlighting a stark contrast to the rapid advancements in data science and machine learning.

Only 50 percent of statistics officials (NSO employees with statistical tasks in their jobs) answered at least half of the exam questions correctly. In two NSOs, this figure dropped below 40 percent. Our questions covered foundational statistical concepts–such as what a standard deviation is.

The absence of foundational statistical competencies in NSOs does not bode well for the ability of governments to leverage rapid advancements in data science and artificial intelligence to enable more data-informed sustainable growth.

How can it be fixed? Recruitment practices play a crucial role. Only 34 percent of statistics officials had their statistical methodology skills or proficiency in statistical analysis software (e.g., R or Stata) evaluated during the selection process. Conversely, 27 percent reported securing their first NSO job at least partly due to connections with friends, family, or politicians, rather than solely on merit. Our data suggests that less meritocratic hiring practices are associated with lower statistical competency among officials.

3. Pressures to modify statistical data for political purposes affect a significant share of statistics officials.

The United Nations (UN) Fundamental Principles of Official Statistics emphasize that official statistics must be compiled and made available on an impartial basis, ensuring that NSOs are protected from political interference. This is sine qua non for high-quality data. The lived experience of some statistics officials is not consistent with this UN principle. When asked whether political pressure is perceived in their NSO to modify statistical data for political objectives, only two-thirds say no.

On the upside, statistics officials–when faced with conflicts of interest–largely prefer to prioritize statistical integrity. When presented with hypothetical ethics scenarios–in which statistics officials face career or family pressures to cut corners or manipulate statistical data–nine out of ten officials prefer an ethical course of action.

4. Many statistics officials are motivated to work hard, but not motivated to stay–we need to pay statisticians in government more.

Our survey reveals that while 78 percent of NSO employees are motivated to work hard, only 46 percent intend to spend their entire career within the NSO. Compensation perceptions play a crucial role in retention: just 21 percent of employees are satisfied with their salary, and only 24 percent consider their pay sufficient to support their household.

Compared to central government employees worldwide, NSO staff report significantly lower levels of pay satisfaction. For example, in the Global Survey of Public Servants, approximately twice as many respondents expressed satisfaction with their salaries.

5. If we want to improve government data, we need better data about the officials producing that data–NSOs can replicate our survey to collect that data.

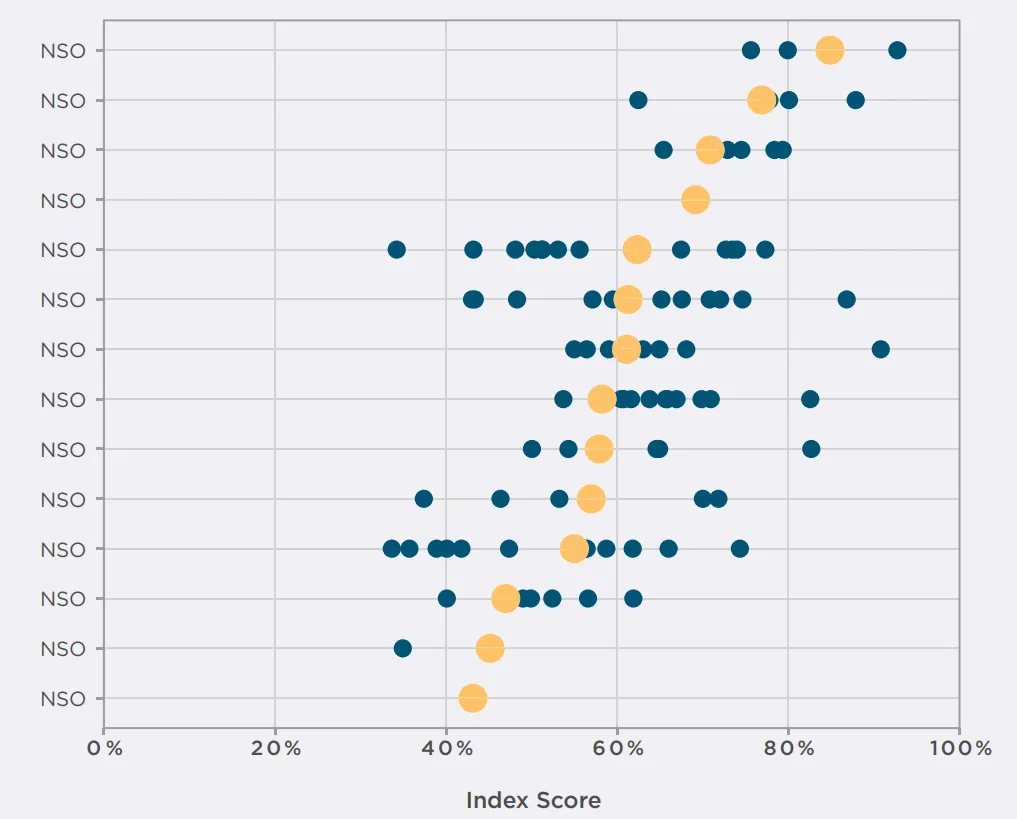

One of our most striking findings is the vast disparity in management quality, motivation, and competence both across and within NSOs. For example, our Quality of Leadership Practices Index ranges from 43 to 85 across different NSOs (on a 0–100 scale) and, within a single NSO, varies from 43 to 87 across departments.

What this means in practice: within a single NSO, some departments are led highly effectively, while others struggle with poor leadership. These disparities highlight the critical need for internal diagnostics. Without employee survey data, NSOs lack the necessary evidence to identify and address organizational weaknesses effectively.

That addressing weaknesses is important in many NSOs is underscored by our data. Governments will only be able to leverage data science and AI advancements if they have statistics officials motivated and competent enough to draw on these advancements to innovate towards ever better data. Our findings suggest we cannot take the presence of such statistics officials for granted–be that in a country or within an NSO in a department. But without data on those statistics officials, evidence improvements in this area are not possible.

To support data collection on statistics officials and data scientists in government, our web portal provides NSOs with resources to implement the employee survey, including the questionnaire, sample diagnostic reports, and an instructional video to encourage participation. By replicating the survey and applying its insights, NSOs can strengthen management practices and enhance statistical capacity effectively and at minimal cost.

For questions about the survey or guidance on implementation, feel free to contact us at [email protected] and [email protected].