For the UK Government to achieve its five missions to make lives better, it must emulate the effective data sharing and linking seen in some schools. Without political leadership to break down data silos and drive collaboration, the potential of government data will remain untapped.

Can the future of government be found in a school in North London? In one respect, maybe. As a governor of my local secondary school, one of my main roles was to scrutinize the data produced each term in support of the school’s mission – to educate local children and close the attainment gap between the best and worst off in this highly unequal part of the world.

The school (a well-run, popular, big state comprehensive) is a model of the kind of data sharing and linkage that, according to the latest report from the UK’s Office of Statistics Regulation (OSR), is all too rare across government. Data from each department and year group, and data on demographics like ethnicity and ‘pupil premium’ – the proxy for income – were combined in a single system to great effect. Teachers and governors could scrutinize which groups of children were doing well or badly in different subjects, design interventions and monitor progress in a continual feedback loop.

This example of data use in UK schools is a microcosm of what, the OSR makes clear, needs to happen across government if the Prime Minister is to deliver on the five missions that are the central platform of his Government’s ambition to make lives better. The value and potential of government data is increasing every day, as public sector data systems are being transformed by the digitalization of public services and the rise of AI. Data has become hugely more useful – meaning that the opportunity costs of not investing in it or using it effectively, in terms of opportunities lost, are rising quickly too.

There has rightly been a lot of interest in the institutional architecture for delivering on the new Government’s missions. Setting up cross-Whitehall groups, with the Prime Minister’s personal involvement, is a necessary innovation to break down departmental silos and make that long held ambition for ‘joined up government’ a reality.

But information is power. If the data needed to plan, implement and monitor the missions remains stubbornly locked away in those same silos, rearranging the chairs around the Cabinet table will only get so far. However, what is emphatically not needed is the Dominic Cummings-esque, Minority-report style central command dashboard of tech-bro dreams. It’s this kind of thinking that has fuelled both public fears and official cynicism about what data can do.

The task for this Government, in line with its stated commitment to substance over style, is rather to make data sharing and linking data from different sources a part of the routine bureaucracy of government. There are pockets of good practice – such as the BOLD program, linking data across health and social care, justice, and housing to understand and deliver better care to people with complex needs. But so far these are isolated pilots that prove the value of the approach, rather than institutionalized practice across government that can bring it to scale.

Governments everywhere are grappling with this challenge and there are some clear common lessons emerging.

1. Technical requirements

At the technical level of government, if data is to be effectively shared and linked, certain conditions need to be applied so that data can be interoperable. Common definitions and standards are key. For example, are all parts of government agreed on official lists of names and places, to group data by country or region? Do different parts of government use consistent ethnicity categories to summarize data that might then be linked with other data? Infrastructure is important too: is the government’s digital architecture up to the challenge of keeping data both safe and usable across the board? There are many highly skilled and committed experts inside government who have been working on this for years if not decades, in governments around the world, and institutional frameworks inside the United Nations and elsewhere dedicated to sharing good practice. This all costs money – is the government prepared to invest in the invisible but critical work of collecting and stewarding high quality data?

2. Institutional commitment

Technical advances and investments can only go so far, unless the institutional context is supportive. Institutional inertia and intransigence is often the stumbling block to effective use of data across governments. Confident leaders who understand the opportunity at hand recognize that data is not a zero-sum game, and that sharing it across government means more and better information for everyone. Senior officials, setting the tone across departments and across government, can remove the excuses for not acting, and drive the necessary institutional changes to get collaboration.

3. Political leadership

The third and biggest challenge is political – and this is where the least progress has been made. As the OSR makes clear, data systems that are linked, interoperable and effective are entirely feasible if leaders want them, and can’t happen if they don’t. Prime Ministers and Permanent Secretaries might see data as something for the techies in the basement, but this would be a mistake, and an opportunity wasted. Political leadership is needed to fully realize the value of data for delivering on political priorities. It’s politics that changes the incentives and creates the room to innovate at the technical level, and the imperative to collaborate at the institutional level.

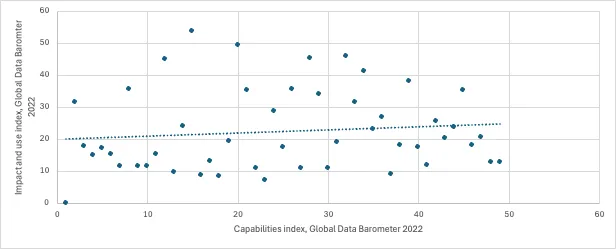

One indication of lack of leadership in this area can be found in the ‘Global Data Barometer’. The data in the Barometer addresses different dimensions of data for public good, and how countries are performing across them. Comparing capacities, as an indicator of the potential for data to be used for good and ‘impact and use’, as an indicator of the extent to which it is actually benefiting people, for the richest and poorest countries in the index, reveals that there is very little, if any, relationship between them (Figure 1). The gap is leadership.

Source: Global Data Barometer (2022). First Edition Report – Global Data Barometer. ILDA.

Politicians everywhere, who have all the advantages of a data system characterized by plentiful skills, strong institutions and good technology infrastructure, are not turning them into impact. This represents huge wasted potential, in this moment of stretched budgets and increasing demand.

For the new mission-driven government in the UK, it’s time to go back to school, quite literally, and make sure that the Government’s data system is up to the job.

This blog was originally published on the Bennett Institute for Public Policy website. Read the original post.