Introduction

Antimicrobials, including antibiotics, underpin modern medicine. But they are becoming less and less effective because of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) — a condition that occurs when infections become resistant to the drugs designed to treat them. AMR is a growing global threat.

By 2050, infections that are resistant to antibiotics could cause 10 million deaths each year.

Yet data on AMR is lacking, which limits our understanding of its burden, hobbles efforts to communicate the urgency of the crisis, and slows national and global efforts to address AMR effectively. To tackle this challenge, the Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS) was launched in 2015. GLASS collects official national AMR data primarily through surveillance systems. However, data remains patchy. More than half of countries in Africa do not submit data on AMR to GLASS. As countries strengthen surveillance data systems and new research on AMR is conducted, complementary approaches are urgently needed to generate quality data on AMR.

Citizen-generated data (CGD) can play a crucial role in plugging these gaps, but it is also critical to gather data that surveillance data will never capture, such as citizen knowledge levels, as well as perceptions and drivers of behavior.

Engaging citizens on AMR — and in the process generating data with them — can help close AMR data gaps, support citizens to take action on AMR, and spur data-driven action by political leaders.

CGD can provide timely and granular data on community issues. It empowers citizens by engaging them in one — or several — stages of the data value chain. While it is a powerful data source on its own, it is also a useful complement to official government data. National statistical offices across the world, including the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS), are already providing data stewardship to producers of CGD, with CGD used to complement official statistics and inform decision-making.

Project overview

AMR is a global issue, but for this project we chose to focus on Kenya because of ongoing commitments to strengthening AMR capacity and the progressive efforts of the KNBS in using CGD as an alternative data source to complement official statistics. While the findings and recommendations are for a Kenyan context, they have broad applications in other countries for AMR response and the use of CGD in decision-making.

From August 2020 to July 2021, with funding from the Wellcome Trust, the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data collaborated with Africa’s Voices Foundation to generate and disseminate insights on AMR in Kenya using CGD. The methods used included a combination of interactive radio shows and SMS/mobile text messaging service across three counties: Kiambu, Kilifi, and Bungoma. These methods were chosen to ensure that data generation involved public engagement and a parallel information dissemination mechanism to increase awareness of AMR while simultaneously collecting insights about citizens’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices relating to AMR.

This report presents the findings from the 10 weeks of interactive radio broadcasting and citizen interaction.

Antimicrobial resistance: A creeping pandemic

AMR arises when infections — caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi, or parasites — become resistant to the drugs designed to treat them. It is a growing threat to public health and to the sustainability of an effective global response to infectious diseases.

In fact, the World Health Organization (WHO) classifies AMR as one of the 10 greatest global public health threats humanity faces.

The Global Action Plan on AMR highlights that the systematic misuse and overuse of antimicrobials have put every country at risk. Without harmonized and immediate action on a global scale, the world is heading toward a post-antibiotic era in which common treatable infections could once again be fatal.

AMR is a growing pandemic, similar to the current COVID-19, and poses a great challenge, as most citizens and community members are unaware of the risk associated with over- or underdosing of drugs and buying drugs over the counter without a prescription.”

AMR is not only a human health problem. The health conditions of people, animals, and the environment are inextricably linked since antimicrobial use and resistance in any one of these spheres can potentially impact the others. Antimicrobials administered to both people and animals inevitably end up in the environment, which can simultaneously impact ecosystem health and potentially foster a reservoir for resistant organisms. A “One Health” approach — which takes a holistic perspective — is therefore essential to fully understanding the drivers, limiting emergence, and mitigating the impact of AMR in different ecosystems.

The data challenges of AMR

There is a lack of data and information about AMR, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). These data gaps limit understanding of the burden of AMR, hobble efforts to communicate the urgency of the crisis, and slow down national and global efforts to address it effectively.

Health surveillance systems and research provide a foundation for a better understanding of the spread of antimicrobial resistance and consumption, but AMR surveillance capability is variable in LMICs. Sub-Saharan Africa and South and Southeast Asia have the least developed surveillance coverage. However, multiple socioeconomic and behavioral drivers of resistance, as well as regulatory and other health system challenges, are also common.

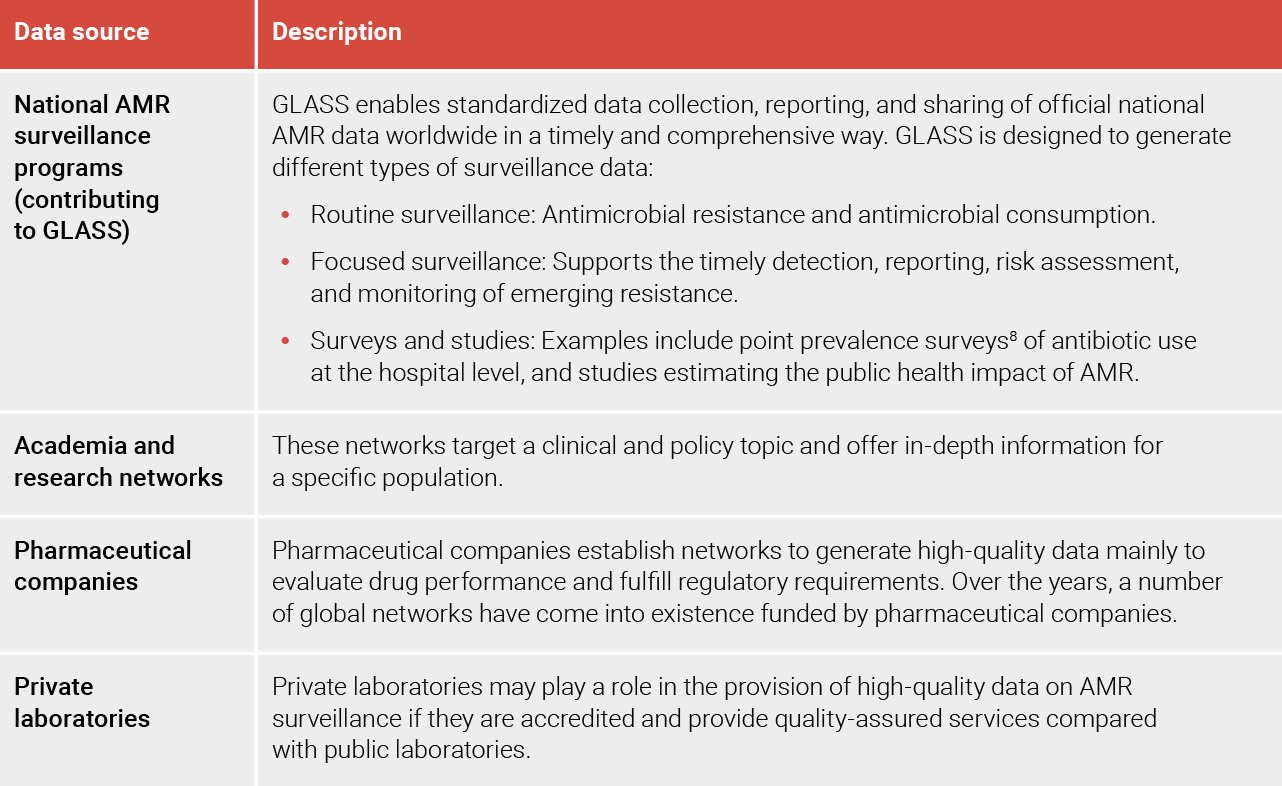

While these data sources are important, they are complex and require highly technical skills to interpret. This makes it even more difficult for decision-makers and citizens to understand AMR and take appropriate action.

While continuing to strengthen quality routine surveillance data is important, complementary methods are needed to address the limitations of this approach, especially where it fails to capture data from the wider population affected by AMR.

Engaging citizens in generating data on AMR can further help close data gaps and mobilize citizen action.

A citizen-generated data approach to AMR

Global action to address AMR is not happening at the scale and urgency needed because public understanding of antimicrobial resistance and its impact is low. Empowering communities with knowledge in turn facilitates the co-development of actions to minimize the negative effects of AMR. Community engagement can and should be data driven to spur action by policymakers to make AMR a priority.

CIVICUS, a global alliance of civil society organizations and activists, defines citizen-generated data as “data that people or their organizations produce to directly monitor, demand, or drive change on issues that affect them. It is actively given by citizens, providing direct representations of their perspectives and an alternative to datasets collected by governments or international institutions.”

Civil society organizations are often the stakeholders convening citizen-generated data projects. CGD is characterized by people’s active involvement in the data production process. It can provide timely and granular data on community issues, supplementing other data sources and helping to shape policies that are responsive to community needs. It creates new spaces for citizens and government to engage and fosters the inclusion of citizens in public decision-making at different levels of government. CGD empowers community members by engaging them in one or several stages of the data value chain: collection, publication, uptake, and impact.

CGD is gaining traction. Many national statistical offices now recognize it as a valuable data source in pursuing sustainable development to help fill evidence gaps. While the approach does not always rely on representative population samples, it is valuable in identifying patterns and guiding official policymaking and monitoring systems.

Key findings

1. Citizens’ knowledge of AMR and its consequences

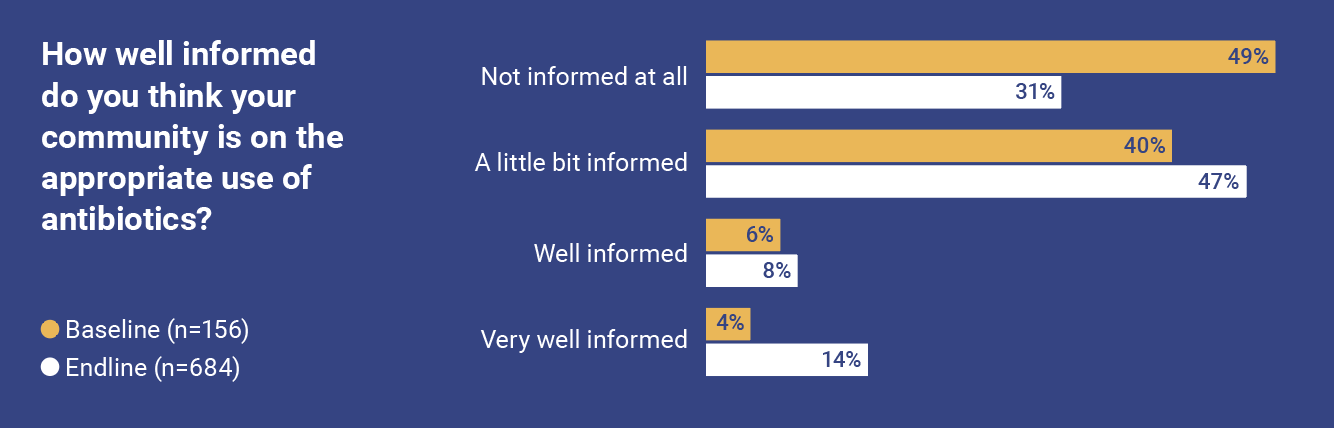

Understanding the scope of citizens’ knowledge is critical to address AMR challenges at individual, community, and societal levels. After the first and last radio shows aired, participants received short SMS surveys (baseline and endline surveys) to measure the level of knowledge about AMR over the duration of the project. This approach allowed us to build on an existing sample of participants who have chosen and consented to participate.

Participation led to an improvement in knowledge of AMR

At the start of the study, community awareness of AMR across the three counties was reported as low.

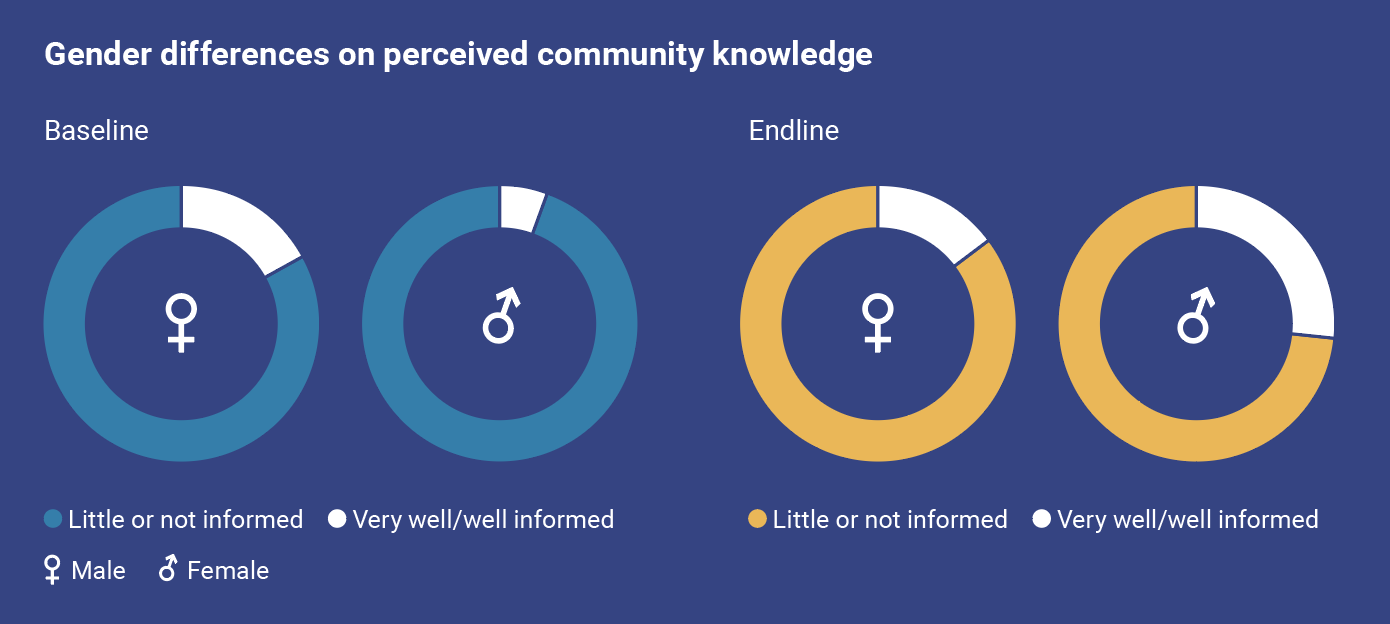

Women reported feeling more informed about AMR than men. This gendered difference was also reflected in the engagement around community awareness. Over the duration of the radio shows, there was a positive increase in the perception by women of the levels of community awareness of AMR. This measure rose from 5.8% at the beginning to 26.9% at the end of the programming. Men did not report a significant change in knowledge over the course of the project.

A general awareness of AMR and antibiotics in theory, but limited in practice

In addition to the baseline and endline questions, we used the weekly radio shows to further measure citizens’ general AMR knowledge level. The findings indicate widespread perceived lack of knowledge about AMR among the general public, highlighted by 31.4% of the respondents. Respondents also reported that there was a need to educate the community on the importance of better understanding AMR and the appropriate health practices.

When asked when antibiotics should be used, over half of participants said that antibiotics should only be taken according to a prescription — a third explicitly said a doctor’s prescription, and almost a quarter of respondents said more broadly that a prescription needs to be followed. A quarter of the respondents said that antibiotics need to be taken when sick or infected, without specifying the illness or the need for a prescription and diagnosis by a health professional.

The LGDs and key informant interviews showed that while respondents know that antibiotics should be taken according to a prescription, this does not translate into practice.

A majority of patients do not follow doctors’ prescriptions; they prefer to purchase medications without prescription by a qualified health worker. They have easy access to over-the-counter antibiotics. They fail to adhere to the recommended dosage (e.g., not completing their course of medication). Some do not use medication at all and rely on traditional healers. Institutional barriers like difficulties in accessing hospitals, low numbers of health practitioners resulting in long queues, and the high cost of health care also mean that knowledge is often not put into practice.

What did the citizens we reached want to know about AMR?

Of note during this study was the number of questions that citizens asked as they participated in the interactive radio programming. This is a strong indication that there is an interest in the topic and that interactive formats such as radio are needed to provide citizens with accurate information on AMR. We analyzed respondents’ questions to break down the specific knowledge gaps related to AMR.

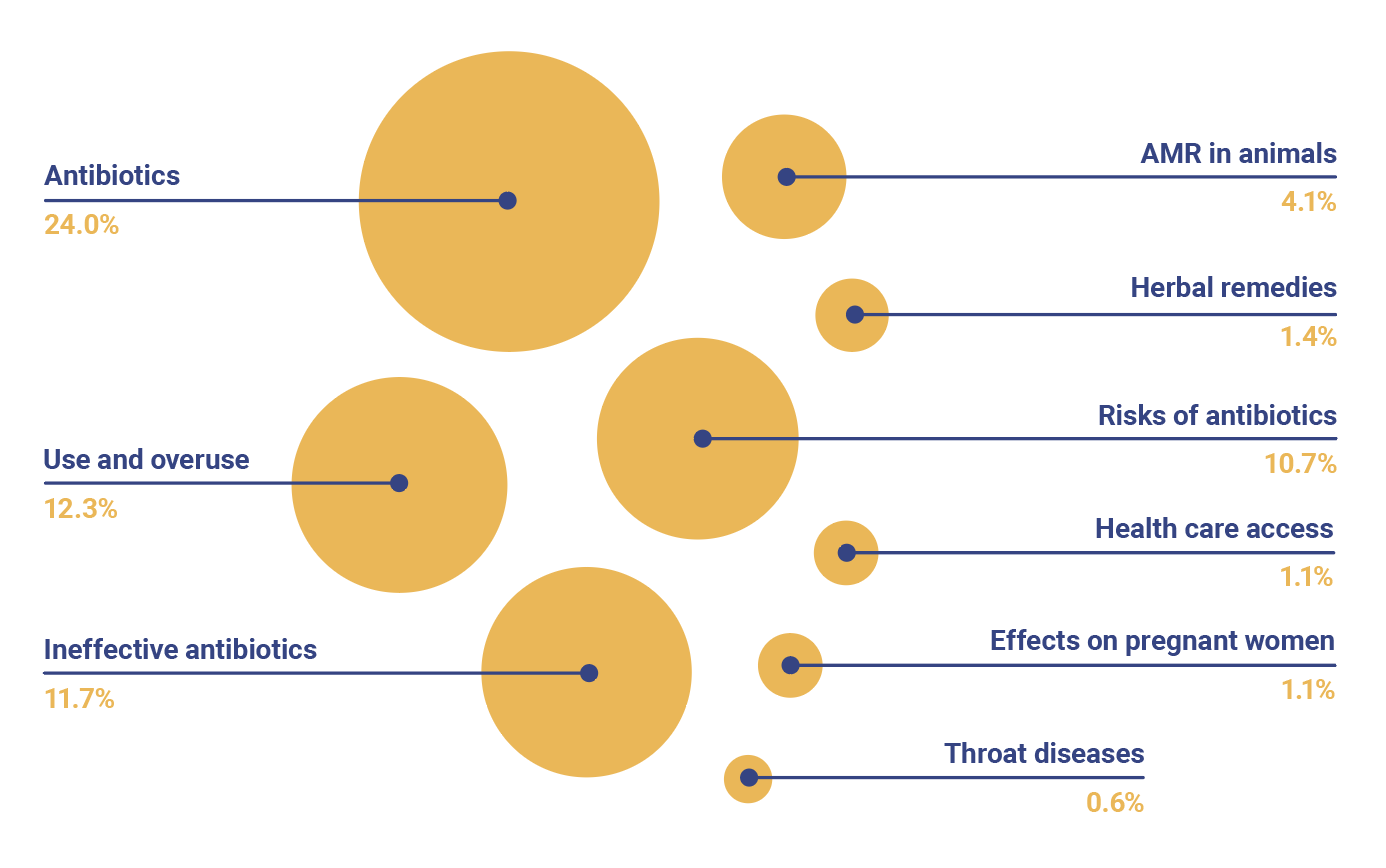

Over half (56.6%) of the questions were on AMR, while the remaining questions (43.4%) were on general medical topics such as causes of flu and children’s ailments, given that the radio show guests were health professionals.

Of the questions on AMR, citizens sought general information about antibiotics such as what antibiotics are, how and when they are used, the difference between antibiotics and painkillers, where certain drugs are sold, and whether particular drugs they were using were antibiotics. They wanted to understand use and overuse of antibiotics, why some of the antibiotics they used were ineffective, and the risks associated with misuse of antibiotics. Others asked questions about AMR in animals, herbal medicines, and how they could access health services.

Female respondents in particular asked about whether antibiotics are safe for pregnant women, their side effects, whether antibiotics can harm unborn babies, and their effects on children.

Kilifi mothers listening group. Credit: Elphas Ngugi.

2. The drivers of antimicrobial resistance

AMR and risky health-seeking behaviors

Respondents were asked via radio: If some bacterial infections become resistant to antibiotics, what are the risks for you and your community?

They identified a number of risks associated with antibiotics use. Respondents reported that medication will not perform well to fight the infections. Secondly, misuse of antibiotics will lead to severe health deterioration, and eventually death. The respondents also reported that misuse of antibiotics will lead to high intake of medication without addressing the underlying health problems, which in turn leads to lowered immunity and even death. Drug misuse was mentioned as a factor in increasing the cost of medication.

The insights from health providers, however, point to poor and even risky health-seeking behavior among citizens. While some seek antimicrobial treatment for any slight illness, most patients seek medical care from health care facilities, where antibiotics are prescribed, too late — when other means (self-treatment through home remedies, herbal treatment, and over-the-counter drugs [which might be antibiotics]) fail. Men are especially reluctant to seek medical care until they are very ill.

An interesting dimension is men avoiding going to hospitals could be an aspect of how society stigmatizes weakness in men by going to hospitals.” — AMR researcher

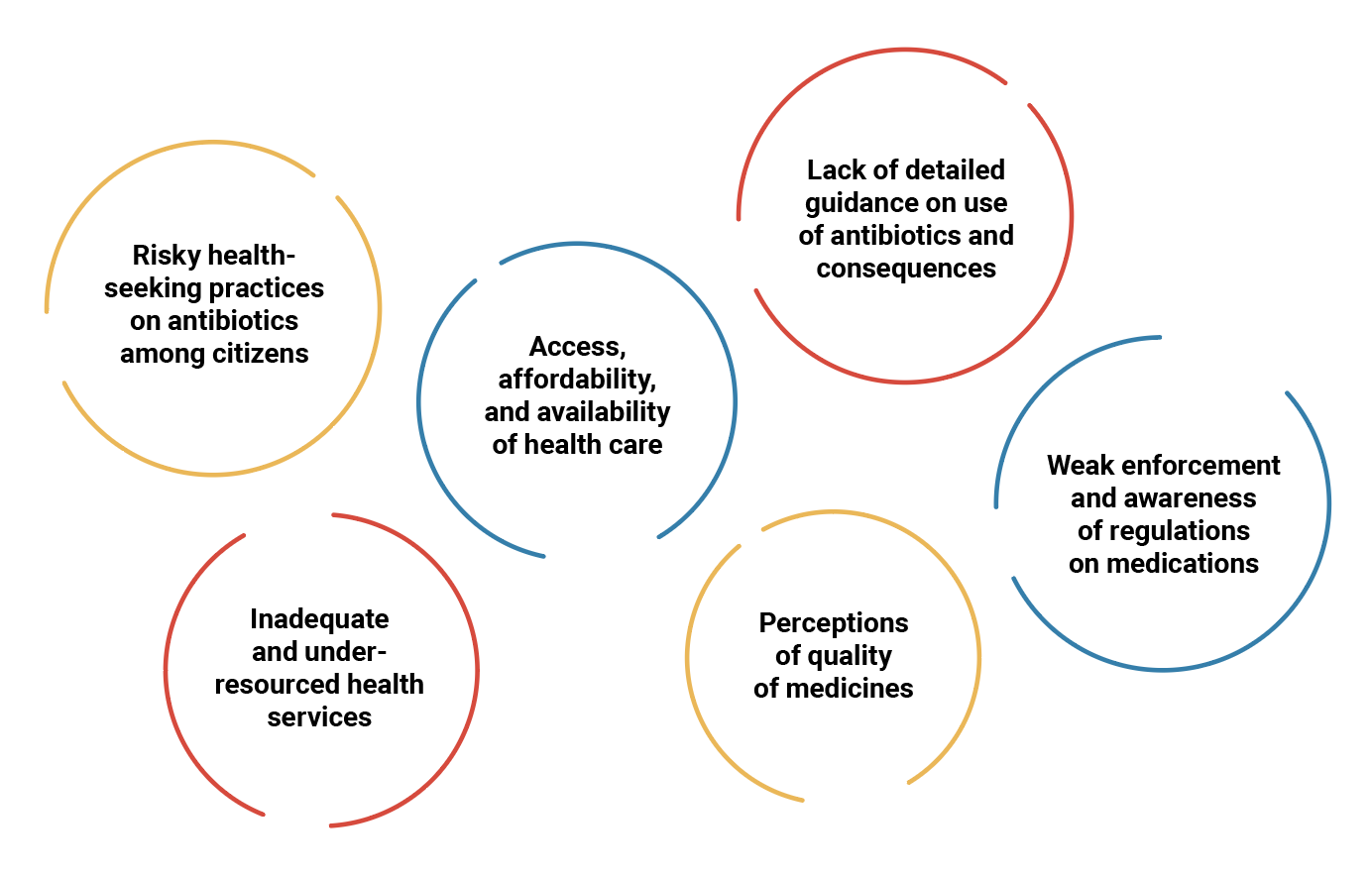

Access, affordability, and availability of health care

Respondents reported that challenges in availability and accessing health facilities, as well as high costs of seeking medical care, discouraged people from going to health facilities when sick. This resulted in self-medication, purchasing drugs over the counter, sharing medication among different children and among neighbors, reusing unfinished medications from previous treatments, purchasing insufficient dosages, and failing to dispose of unfinished medication.

Mothers in particular seek antibiotics from chemists for their children. Health care workers were of the opinion that people share medication because it saves them the cost of purchasing their own medication and prevents them from incurring additional costs from the visit required to obtain prescriptions.

Guidance is often too vague or missing completely

Citizens often obtain knowledge about AMR only through interactions with health workers. While this signifies an appropriate reliance on health care professionals, these interactions are not sufficient for patients to properly follow the advice provided during prescription; this lack ultimately leads to misinterpretation and misuse.

Furthermore, citizens frequently perceive the state of their health in terms of how they are feeling, and therefore do not demand laboratory tests or seek a professional diagnosis (which would cost more). In addition, as soon as a patient is feeling better, he or she may end treatment prematurely without understanding how the medication works.

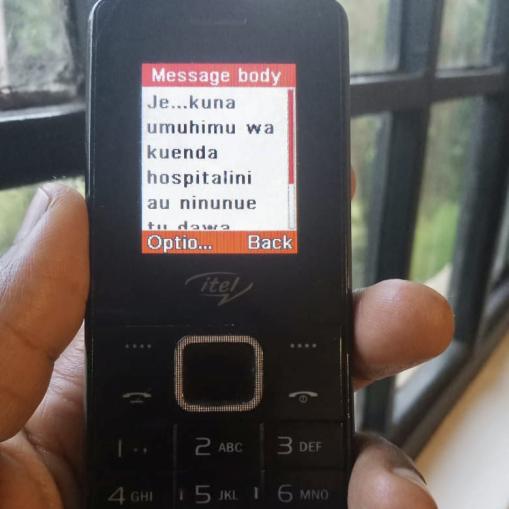

Je....kuna umuhimu wa kuenda hospitalini au ninunue tu dawa kwa chemist? “Is it necessary to go to a hospital, or should I just buy medicines from a chemist?” — Woman, 32, Kilifi South

Weak enforcement and awareness of medication regulations

Citizens were asked, “What should the county government do to ensure there is an appropriate use of antibiotics in the county?” Among participants, 13.3% said that the government should put in place and enforce regulations on the sale and use of antimicrobials.

Citizens feel that effective regulation is important in addressing AMR, but this can only work if the health systems are functional as well. For instance, respondents reported that in a significant number of public health facilities, patients are often asked to buy drugs from specific private pharmacies. This type of prescription presents various risks, such as pharmacies selling only specific types of drugs or being promoted while operating without proper licensing.

Although regulations exist, the level of enforcement and awareness was said to be low. Respondents also perceive existing regulations as unresponsive to the needs of the health sector. For example, some health practitioners felt that while it is advisable for people not to buy drugs over the counter, when citizens have no health facilities near them, pharmacies become their first call for assistance.

Perceptions of the quality of medicines

Close to 10% of citizens who responded via SMS think that infections are becoming resistant to antibiotics because of the poor quality of medications in the market.

For example, some believe drugs to be of poor quality because they are generic and therefore cause further resistance. Health care workers also reported that some citizens relied on traditional health care practices and herbal remedies to treat infections.

The quality of medicines is also perceived to be partly driven by the profit seeking of pharmaceutical businesses, especially at the community level, where regulation enforcement is weak.

Inadequate and under-resourced health services

During the LGDs, participants said that health care workers do not have time to provide adequate information on how to use drugs due to long queues and heavy workloads.

Health professionals’ limited numbers restricts the time they have to interact with patients and share knowledge on AMR, how to use drugs, and other good health practices. The dearth of health care workers also means that not all citizens have access to health professionals.

Respondents, particularly from Kiambu County, also pointed to the need to equip and resource public health facilities across the country. Currently, they rate services in most public health facilities as poor. With more functional health facilities, citizens will be able to access professionals who can give reliable prescriptions and work within an enforcement framework.

Lack of trust in health professionals

Health care workers in the listening group discussions reported that it is common for citizens to demand specific medication in a specific form — for example, an injection — and when they don’t receive the requested treatment, they get frustrated and question the competence of health care workers. Mistrust is also driven by traditional beliefs, such as in the value of healers and herbal medicine, which often lead to treatments that conflict with those of medical professions.

The aspect of AMR and herbal medicines really stood out for me in your study. Most communities in Kenya use traditional medicines as part of care, and it becomes very difficult to change people’s mindset.” — AMR researcher

Kiambu health care workers AMR capacity building workshop. Credit: Elphas Ngugi.

3. Cross-cutting issues

A One Health approach to AMR

AMR can spread through the food chain and the environment. Therefore, understanding the role that animal health and the environment play in AMR (a One Health approach) is crucial in preventing infections and the further development and spread of AMR. While this study emphasized the effects of AMR on human health, we also looked at the One Health approach as a cross-cutting issue.

Our respondents reported misuse of antibiotics on animals, largely due to a lack of knowledge.

Antibiotics are used to treat various ailments among chicken and dairy cows (such as respiratory illnesses and mastitis). When animals are undergoing antibiotic treatment, owners are often advised to avoid consuming or distributing the products from these animals (meat, milk, or eggs), but many farmers do not adhere to these withdrawal periods, thus exposing consumers to AMR. In addition, farmers don’t always seek professional veterinary services due to costs, and instead obtain medication from agrovet supply outlets.

Key recommendations

The findings from this study offer recommendations for action, drawing on a combination of feedback from the radio shows, SMS, brown bag with the research community, and town hall meetings. While these recommendations are drawn from a Kenyan context, they have global applications.

Recommendations for citizens and communities

- Feel empowered to play a role in tackling AMR by changing practices in accessing, using, and misusing antimicrobials. This includes following prescriptions, maintaining hygiene, and educating other community members.

- Proactively engage in efforts to gather citizen-generated data. Civil society organizations should engage with citizens as part of the process and draw on them as an important data source.

Recommendations for national and subnational government policymakers

- Make investment in AMR a public health priority. Specifically, investment should target strengthening laboratory networks to enable access to surveillance and monitoring of infections; equipping health facilities with sufficient medication and health care workers; and making health services affordable.

- Promote AMR stewardship. Specifically, policymakers should incorporate citizen engagement in AMR decision-making, policies, and budgets. Additionally, there should be a focus on enforcing and raising awareness of regulations to tackle AMR.

- Embrace citizen-generated data as a critical source on a par with official data sources. Policymakers should consider partnering with civil society organizations to collect, analyze, and use CGD to inform programs, monitor their effectiveness, and engage citizens.

Recommendations for health care workers

- Drive quality patient engagement on AMR to tackle misinformation and improve levels of trust with citizens. This includes providing patients with comprehensive information, such as explaining the importance of adhering to prescriptions and dosage so that patients use antibiotics properly.

- Take a holistic approach in addressing AMR. This requiresunderstanding the role of community engagement and drawing on lessons from CGD to inform interactions with patients and communities.

Recommendations for the research community

- Explore ways to incorporate citizens’ voices in research studies that target challenges on AMR, especially in hard-to-reach areas such as arid and semi-arid lands.

Conclusion

There is a clear association between knowledge and the use and misuse of antimicrobials. This project demonstrates a discernible benefit to public engagement on AMR. Even within the span of 10 weeks, the project in Kenya saw an increase in knowledge on AMR across the three counties we targeted. Citizens have a genuine quest for knowledge on AMR, as indicated by the number of questions they asked during the radio shows. This indicates that targeted and consistent public engagement can reduce knowledge gaps and, ultimately, influence behavior change to address AMR.

Our findings indicate that the challenges of access and availability of health facilities, as well as the high costs of seeking medical care, lead to poor health-seeking practices that exacerbate AMR. This harmful dynamic is further reinforced by inadequate and under-resourced health facilities, leading to long hospital queues and leaving health care workers no time to engage meaningfully with patients on AMR. Citizens feel that effective regulation, enforcement, and awareness are important in addressing AMR, but these solutions can only work if the health systems are functional as well.

The recommendations highlight that AMR is a shared responsibility.

Citizens, policymakers, health care workers and the AMR research community all have important roles to play in tackling AMR in their communities, their countries, and beyond. As expected, an engaged citizenry leads to more emphasis on government responsibility in prioritizing investments and policies to tackle AMR and strengthening health systems. Citizens know that the onus is on them to change their practices on AMR but to also hold the government to account on prioritizing AMR and the regulation of antimicrobials. Health care workers need to properly engage and inform citizens on AMR and its dangers. The AMR research community needs to embrace CGD in understanding nuances on AMR and filling data gaps where surveillance data may not suffice.

This study has reinforced the value of citizen-generated data in providing insights on issues such as AMR that matter to citizens and closing data gaps. By following rigorous standards and methods, the findings resonate with what the AMR research community has found using other types of data collection.

CGD is a valuable approach, as it creates new spaces for citizens and government to engage and include citizens in public decision-making at various levels of government. CGD empowers community members by engaging them in one or several stages of the data value chain — collection, publication, uptake, and impact. It offers an important complement to official data produced by national statistical offices in driving forward a data revolution for sustainable development.

Looking forward, the value of CGD can be further supported through national statistical offices providing stewardship to producers of CGD. Stakeholders in AMR can tap into CGD more deeply to help them understand and influence the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of citizens on AMR.