CGD expands what gets measured, how, and for what purpose. CGD initiatives cover areas from cartography to government policies, public services, and environmental research. CGD initiatives create new types of relationships between individuals, civil society organizations, and public institutions. These initiatives include local development and educational programs, community outreach, and collaborative strategies for monitoring, auditing, planning, and decision-making. CGD can inform several areas, including community engagement and community-based problem solving, planning, and strategy development, as well as improvement to public services. The quality of CGD can be comparable to official data collections, provided the quality of tools is high enough, there is sufficient training on the tools, and quality assurance is provided.

Research gaps

This project began with a scoping phase to understand the AMR landscape in Kenya. This phase involved a literature review to identify the data gaps (details are in the full report Annex B) and interviews with key stakeholders, and it culminated in a workshop in October 2020.

Through this process, the following key data gaps and research questions were prioritized:

- Knowledge around disease and drug resistance

- What is citizens’ knowledge of AMR and its consequences?

- What is citizens’ knowledge of antimicrobials and reasons for seeking antimicrobials?

- Reason for use/misuse of antimicrobials

- What are citizens’ practices in using antimicrobials?

- What are the prescribing and dispensing habits on antimicrobials?

- What is the level of adherence to regulations on drug use and misuse?

- Accessibility and availability of antimicrobials (especially in public sector)

- What are the drivers for stocking and selecting antimicrobials at the pharmacy or health facility?

A One Health approach and the gendered dimensions to AMR were also identified as cross-cutting issues to interrogate.

CGD methods

This study used interactive radio, SMS, listening group discussions, and key informant interviews to generate data. These methods were used for the following reasons:

- Radio is the most consumed media source in Kenya and is a powerful medium for influencing culture, beliefs, and values, and it is a tool for economic growth and development.

- Most Kenyans also have access to a mobile phone and could therefore interact with the radio shows through free SMS.

- Radio is the right medium for translating technical subject matter into everyday language. For a complex topic like AMR, the use of radio was important to simplify the language and interact with a wide range of citizens.

- The realities of COVID-19 meant that remote data collection was essential. Given the COVID-19 restrictions on in-person gatherings and travel, interactive radio and SMS were a workaround to face-to-face meetings.

The value of interactive radio and SMS

Africa’s Voices Foundation has been using interactive radio, in which radio debates are driven by citizen input via SMS, since 2015. This is a mixed-media engagement technique to create actionable social evidence. By curating inclusive discussions through digital, interactive channels, Africa’s Voices Foundation empowers citizens to share their voices, on their own terms and language, at scale.

The significant improvements in knowledge while engaging in interactive radio programming — as a citizen-generated data approach — are well documented. Interactive radio builds social spaces in which audiences can perceive and actualize change through interactivity and audience engagement. Its outcome is twofold: creating awareness on a health issue like AMR and increasing knowledge on the same. Audience members hear positive narratives from others in their own communities. Moreover, content is informed in real time based on analyses of audience perspectives — by, for example, involving specific health experts to provide knowledge and highlight government policy on AMR as well as to answer questions from citizens.

Listening group discussions (LGDs) targeting mothers and both human and animal health care workers were conducted in tandem with live radio shows. LGDs were useful to capture insights from these specific target groups, as they are key stakeholders in addressing AMR. Through the LGDs, participants discussed the radio show topics and responded to the weekly questions. Key informant interviews were conducted with human and animal health experts, health care workers and decision-makers to complement the data from the radio shows and add contextual information to the insights.

Design and data collection

At the beginning of the data collection phase, the research team identified the most appropriate radio stations for the project. The selection of radio stations was informed by existing working relationships, the stations’ popularity, value for money, programming in the local languages spoken in the counties of study (Kiswahili, Kikuyu, and Luhya), and their coverage areas. The project deployed 10 weeks of radio programming in the three targeted counties of Kiambu, Kilifi, and Bungoma. The choice of the three counties was guided by the following requirements:

- To align and inform a Clinical Information Network on AMR (CINAMR) project that includes these three counties;

- To represent socioeconomic and geographical diversity, as these counties have a mix of rural and urban populations;

- To select counties with existing investments in AMR stewardship and activities.

- To conduct the project in a county with some level of budget transparency based on the Kenya County Budget Transparency Survey.

The research team developed a strategy to help inform the design of the radio series and the questions to be asked of listeners on every show. The radio shows were designed to be one-hour sessions that aired during prime-time hours and included guest speakers who were AMR health experts or policymakers.

Feedback loops

This project deliberately included an information dissemination phase to ensure that the data generated was shared back with the communities and key stakeholders at local and national levels to increase knowledge and drive data use and action. At the end of the 10 weeks, the research team sent an SMS to participants providing information on the main insights resulting from the study. In addition, we held a town hall meeting in each of the counties (except in Bungoma, due to COVID-19 restrictions) and at the national level.

These outreach efforts were designed to share the findings, validate them, and come up with joint recommendations. These meetings brought together our target stakeholders: citizens who participated in the study, community leaders, county and national government officials (including those responsible for AMR prevention and control in human and animal health), civil society, and the media. In addition, a brown bag lunch was hosted with the AMR research community to share the findings and promote CGD as a complement to AMR surveillance data.

Methodological limitations

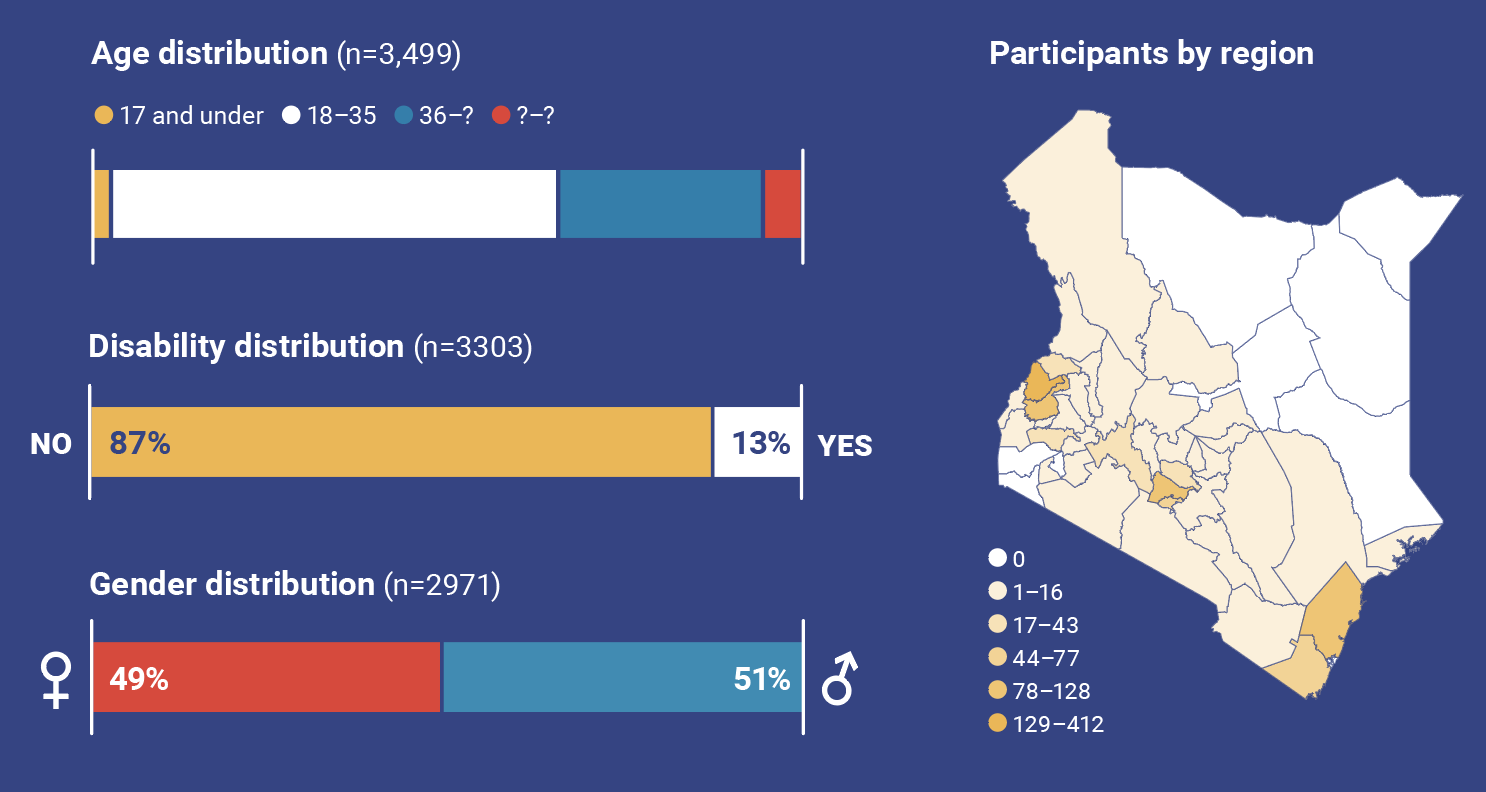

Like other research with community engagement components, CGD relies on self-reporting, and therefore the data can often be subjective. Not all participants respond to all demographic questions, and this limits the level of detailed disaggregated analysis against all demographic indicators.

Information about knowledge, attitudes, and practices by nature is subject to change and must be treated as a snapshot in time. However, because this project included data collection over a period of several weeks, some insights indicating changes in knowledge over time are useful in understanding patterns and trends.

The project had the dual objectives of disseminating information and collecting data. However, it was not designed to measure the impact of the information via the radio shows. Behavior change often takes a long time to manifest. While this project was designed with the hope that it would contribute to behavior change through an increase in knowledge on AMR, the time frame of the project limits any measurement of the interventions’ effectiveness.

While care was taken in selecting radio stations that cover the three counties, radio frequencies go beyond geographical boundaries to reach neighboring counties; listenership therefore went beyond the three counties. It also does not ensure a representative sample of the population given access and variations in use of radio. Given these factors, the findings are not intended to be interpreted as statistically significant or representative of the populations in those counties, but rather as general insights that indicate patterns in knowledge and drivers of AMR.