When pests and disease ravage livestock, farmers are often left struggling to make ends meet. Pest eradication campaigns can fail because infested areas are insufficiently mapped and targeted so small pockets of the pest population survive and re-grow. Better data can lead to better targeting and, ultimately, to complete eradication. Fewer pests leads to increased farmer income and better food security and shifts investment decisions to change the trajectory of future prosperity.

It is commonly agreed that data is valuable, but quantifying its precise value is notoriously difficult. In resource-constrained settings, data production, data systems, and capacity are routinely deprioritized in favor of investing in interventions that lead to quicker, more visible outcomes. Ultimately, those who hold the purse strings need to be persuaded of the impact of a data investment. Decisions not to invest in data result in ineffective pest control measures and unmitigated threats to livestock, which lead to exacerbating hunger, more cattle wasting, and other negative effects.

In Senegal, better data allowed the Government of Senegal to tackle the decades-old challenge of eradicating tsetse flies that threatened livestock and farmers’ livelihoods. The Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data is committed to sharing stories like this one that demonstrate the relationship between better data and positive economic, social, and environmental outcomes for people and planet. As this body of evidence grows, we leverage these stories in our advocacy and engagement with influential decision-makers globally and nationally.

This case study details how satellite data was mobilized to eradicate tsetse flies in the Niayes region of Senegal.

Context

The Niayes region in northwestern Senegal forms a coastal strip which has particular climatic conditions that allow intensive cropping and cattle breeding even during the dry season. In addition to local breeds, important non-native cattle populations are maintained for milk production. The area is also known for high densities of horses which are of high economic value and used to transport food crops. However, the cost effectiveness of maintaining these animals has been continuously threatened by exposure to African animal trypanosomiasis (nagana), a wasting disease transmitted by the tsetse fly and considered one of the most important constraints to cattle production in infested areas. In 2006, a parasitological and serological survey of resident cattle showed up to 90% herd prevalence rates of the disease.

Eradication campaigns are essential tools to control such diseases. However, they are expensive and if the target fly populations are not truly isolated from each other, cleared zones are gradually reinfested by tsetse flies from neighboring areas and the eradication campaign fails. The first attempt to eliminate tsetse flies from approximately 150km of habitat in the region was undertaken in the 1970s using selective bush clearing and residual ground spraying. While no flies were detected immediately following the campaign, they reappeared in the 1980s. A second campaign was then launched using insecticide spraying and traps. However, the flies re-emerged by the late 1990s with severe consequences for livestock and farmers’ livelihoods. A key reason for the failure of these efforts is that the campaigns were initiated when only half of the infested areas had been identified and the eradication activities did not reach the entire target population.

Data as the missing link

Given the isolated nature of the Niayes tsetse population, resurgence after the two campaigns in the ‘70s and ‘80s described above were due to population build-up from small residual pockets inside the Niayes area. This indicates that both efforts lacked comprehensive and precise data about the spatial distribution of the flies within the region, limiting the ability of the activities to target the entire population.

Following learnings from the previous campaigns, the Government of Senegal initiated a new tsetse eradication project in the Niayes region in 2005. This project started with a feasibility study in 2006 to assess the possibility of creating a tsetse-free zone in the Niayes region. The study was supported by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), the International Cooperation Centre of Agricultural Research for Development, and the Government of Senegal through the Senegalese Institute for Agricultural Research and the Directorate for Veterinary Services. Following a period of trials, training, and preparation, beginning in 2012, the project implemented the sterile insect technique, which involves releasing mass-produced sterile male flies in the infested areas to halt reproduction and ultimately eradicate the flies. This method is considered one of the most environmentally friendly tactics. The results of this project fit into a FAO/IAEA pan-African tsetse fly eradication campaign launched in 2001.

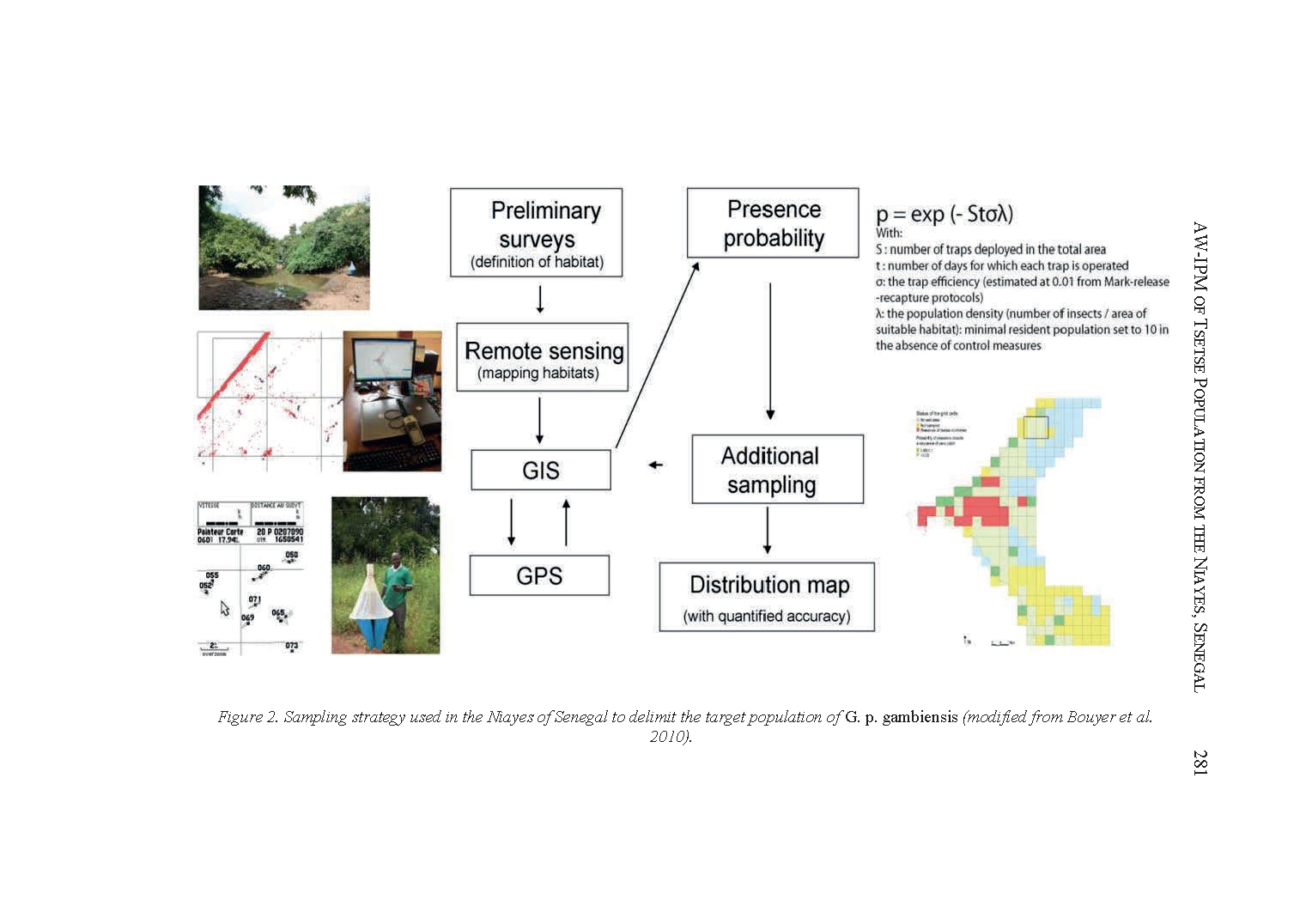

The success of this project was driven by the precision and accuracy of the feasibility study conducted from 2006-2010. Specifically, the study used innovative data and methods including satellite data, geographic information systems, and mathematical models to identify the spatial distribution of the flies and confirm isolation of the target population. These data and methods allowed the project to increase efficiency by covering a large area with few resources, reduced costs, and improved granularity and accuracy of insights, ensuring that the eradication strategy was targeted and thorough. The study also confirmed that the tsetse population in the Niayes region was isolated from the southern part of Senegal by dry areas where the fly could not survive. This meant that, once the flies were eliminated in the identified areas, the risk of re-infestation was very low, ensuring success of eradication activities.

“As these [tsetse flies] are very sensitive to environmental conditions, the collection of temperature, rainfall, vegetation, and other environmental data was essential. Satellite data offers the solution to provide information on this type of parameters.” – Dr. Assane Fall, Institut Sénégalais de Recherches Agricoles, Department of Bio-Ecology and Parasitic Pathologies

Tsetse flies cannot survive without suitable habitats, including forest tree cover and presence of fresh water. This means that identifying environmental conditions in a given area would indicate the presence of flies as well as the potential for development of flies. Satellite data allowed the team to identify vegetation and wet areas across the seasonal cycle through a singular data source. In the absence of satellite data, the team would have had to use a combination of ground surveying, potentially using drones to map the area, and sensors to collect data on temperature, humidity, rainfall, vegetation, and other characteristics. Even with these multiple methods, it would have been difficult to cover the entire area, particularly at the level of precision required. “So, using satellite data has the advantage of collecting all the data we need through a single download,” explained Dr. Fall.

The wet area classification from the satellite data enabled the project to detect tsetse flies in unexpected sites, such as military camps where sampling would not have been implemented otherwise. In addition, some areas identified as wet areas were remote and would not have been covered through traditional ground surveys. During implementation, these areas required the use of GPS to locate the sites that were sometimes several kilometers away from established tracks.

“Satellite data has the advantage of offering a wide range of data types. In addition, they made it possible to have an acceptable precision for our project in order to prevent the omission of favorable areas capable of harboring flies that can recolonize the area,” says Dr. Fall.

The target zone for the project covered 1000 km2. Using satellite data and modeling techniques, the study was able to restrict the area that needed to be surveyed to 4% of the total surface area covered. This meant significant cost savings for data collection activities. Use of satellite data and these innovative methods were estimated to have reduced the sampling costs by 90%, while optimizing the efficiency and accuracy of the insights.

Sampling strategy used in the Niayes of Senegal to delimit the target population of G. p. gambiensis (source).

Impact

In an FAO report on the project, Baba Sall, then Project Manager and Head of the Animal and Health Section in the Ministry of Livestock at the time, said, “Eradicating the flies will significantly improve food security, and contribute to socio-economic progress.”

A cost-benefit analysis of the project found that the eradication of the tsetse fly in the Niayes region would result in annual benefits of 2.8 million Euros. The cost of the project was estimated to be 6,400 Euros per km2. However, the study found that this was significantly outweighed by the additional income of 2,800 Euros per km2 to farmers on an annual basis, meaning that the project would pay for itself in 2.5 years. Research estimated that income of the rural population would increase by 30%, as farmers would be able to sell more milk and meat.

The eradication project has allowed farmers to switch from less productive disease-resistant cows to more productive imported breeds. Before the successful eradication of the flies, farmers kept local breeds despite their low milk and meat production and low reproductive rates because they are naturally tolerant to trypanosomiasis. However, now they are replacing breeds that produce 1-2 liters of milk a day with imported breeds that can produce between 20-40 liters. In addition to reducing the cost of treating animals, farmers have substantially increased both productivity and income. The improved milk and meat production of those breeds has enabled farmers to maintain smaller herds, reducing the grazing pressure on the fragile ecosystem without sacrificing income.

Loulou Mendy, a pig farmer in the area quoted in an FAO publication said, “Life has become more comfortable not only for the animals, but also for the farmers, now, we can even sleep out in the open. This was unthinkable before because of the tsetse bites.”

Within Senegal, Dr. Fall and his team report that the benefits of satellite data have been recognized and have since been used in multiple other projects to model animal diseases. In particular, it has been used to map the risk of diseases such as Rift Valley fever, foot-and-mouth disease, and the avian influenza to help decision-makers design and implement interventions. Internationally, the geospatial data has been incorporated into similar projects in a number of countries including Uganda.

Dr. Seydina Ousmane Sene contributed research for this data story.