This article is also published here on August 31, 2021 by Data-Pop Alliance. It's the second edition of the Gender Data Series, which comprises interviews, videos, and opinion articles from experts to bring light to issues at the intersection of gender and data including health, migration, livelihoods, and gender-based violence (GBV). A related webinar, organized by UNU-IIGH, the University of Cape Town, and BBC Media Action, is available here.

Lockdowns, quarantine, and travel restrictions have been crucial tools in limiting the spread of COVID-19 globally. However, these policies have unintentionally created a ‘shadow pandemic’ of gender-based violence (GBV)—including increases in violence against women and girls. Existing efforts to tackle these forms of violence may even have regressed during COVID-19, requiring countries to explore new and innovative solutions to this important issue.

In countries around the world, healthcare systems and societies have witnessed a ‘quarantine paradox’ whereby policies to keep people safe have also led to serious harm for some. The pandemic has led to economic uncertainty and increases in unemployment, as well as to the reinforcement of existing harmful gender norms and government restrictions that have prevented women from leaving their homes. These, combined with the deprioritization of life-saving support—including clinical management of rape and intimate partner violence, reproductive health and shelter services—have cost lives. Around the world, COVID-19 has restricted women’s access to healthcare even as the need has increased. In some countries, calls to GBV hotlines, mobile-apps, and use of low-tech alert and support services have risen significantly.

Combating the shadow pandemic requires a whole-of-government and whole-of-society response. Technology and innovation also have a key role to play. With COVID-19 driving increases in digital transformation and digital service delivery, these tools have also been used to assist in the prevention of and response to GBV, including reporting and supporting services for survivors. These tools are likely to continue to be an important resource for women, policymakers, and support agencies after the pandemic. They also play an important role when coupled with face-to-face and low-tech services to reach the 390 million unconnected women in low- and middle-income countries. However, we need to ensure that these tools are used effectively and inclusively. To do that, it’s important to first understand more about governmental mitigation approaches to GBV during the pandemic.

How pandemic policies have tried to tackle gender-based violence (GBV)

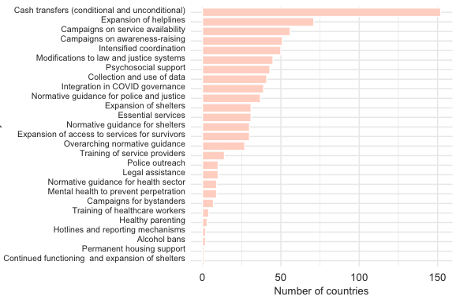

Governments around the world have had to quickly identify, expand, and implement policies and approaches in the context of COVID-19. The COVID-19 Global Gender Response Tracker compiled policy measures that have been planned and/or implemented by governments worldwide in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Globally, the top three interventions to tackle violence against women during the pandemic—beyond financial support—have been the expansion of helplines (37 percent of countries) and running campaigns to promote support service availability (29 percent) and to raise awareness about GBV (26 percent).

Chart data from UNDP and UN Women's COVID-19 Global Gender Response Tracker.

Some of these interventions rely on digital technologies, such as the use of social media and other platforms to highlight services, raise awareness, and enable survivors to report instances of violence. The most common digital channel is mobile phones, which have been used in nearly 70 percent of digital responses to GBV during the pandemic, globally.

Chart source: O’Donnell, 2021 Gender and Digital Health webinar.

However, technology solutions do not work for all survivors, even those with digital access and high digital literacy. The conditions required to access digital services preclude many women, particularly those whose devices are shared with or monitored by abusers, and others who do not have privacy in their homes, to reach out to report and support services. Women and girls living with disabilities and in refugee camps are overrepresented in this group.

How data can drive responses to GBV

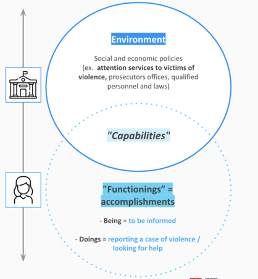

Increases in usage of digital services have also resulted in data that can be used to drive responses and decision making. A study from Data-Pop Alliance analyzed administrative and non-traditional sources of data from México City, Bogotá, and São Paulo to better inform public policy around violence against women at home. Acknowledging the rise in cases since the start of the pandemic, the study explored human “capabilities” (as defined by Amartya Sen) to achieve well-being, in this case, as expressed through actions of seeking help and reporting experiences of violence. Through analyzing data from the “Línea Mujeres” helpline, police reports, and 911 emergency calls, the team developed a model that explored the impact of demographic and contextual risk factors to report violence against women and girls.

Analyses of these results show that the data sources considered reflected biases related to capabilities and opportunities to report GBV. The following factors were associated with greater reporting and registering among GBV survivors: age (30-49 years old in Mexico City and São Paulo, 20-40 in Bogotá); marital status (being single in Mexico and Bogotá); access (proximity) to support services for victims (Mexico City, São Paulo); people cohabitating in a living space (less than three people sharing a room in São Paulo), and greater mobility (less restrictions).

Figure shows Data Pop-Alliance study authors' application of Amartya Sen’s Capabilities Model to the concept of reporting capabilities. It suggests that women depend on “functionings” and the “context” or “environment” to report incidents of violence.

Additionally, this study revealed important gaps in GBV reporting (such as lack of availability to data sources, different and unclear conceptualizations of GBV, and data standardization issues that limit comparability of datasets, among others) and other crisis data, particularly during disasters and emergencies. So, how do we improve collection, management, and analysis of GBV data, especially to drive effective policy making, service delivery, and response? The Data-Pop Alliance study highlights four recommendations. In particular, we need to improve:

- Access to data: improve transparency of data for responsible sharing.

- Coverage and data disaggregation: increase spatial and temporal granularity of data to allow time and geographical analysis.

- The quality of data: include more demographic information including gender and several indicators to improve our understanding and conceptualization of GBV.

- Data governance: adopt further ethical guidelines and promote the use of data to inform policies.

The role of Big Tech

In order to best support women experiencing GBV, efforts have focused on platforms familiar to many women (reaffirming several of the Principles for Digital Development). Twitter was one social media platform at the forefront of information dissemination during the pandemic. The organisation launched a dedicated gender-based violence search prompt as part of its #ThereIsHelp campaign to connect users with local hotlines and support. This has now been deployed in 27 countries and 30 languages in collaboration with local NGOs, governmental agencies, and UN Women. This approach has been particularly effective in Thailand where the initiative has connected GBV survivors with local law enforcement, government agencies, and NGOs who can provide longer-term services and assistance.

These solutions are not a panacea. They rely on women with suitable devices and access to them as well as the digital skills and confidence to use them effectively. In the context of emerging digital tools and rising GBV cases, it is important to focus on those affected by the gender digital divide. More digital efforts aimed at GBV prevention are also needed, in addition to further knowledge about the impact of policies and digital interventions on GBV during the pandemic.

Work conducted in South Africa, for example, highlights the complexity of using data generated in crisis to drive sustainable response. In this case, the use of different digital platforms seemed to have contributed to misestimating the cases of GBV. While police data in South Africa showed a reduction in GBV-related calls, this may have been due to reallocated police attention away from domestic cases to other GBV initiatives available (thereby spreading data across a number of different services) and movement restrictions. This nuance reaffirms the importance of exploring the detail and context, through approaches such as those used by the Data-Pop Alliance.

That said, the global efforts of Twitter and other Big Tech organizations play an increasingly central role in an ever-growing toolkit to tackle GBV and other forms of violence against women. This role is likely to increase as these platforms continue to grow.

Learning from the past to design future innovations

As policymakers continue to design digital interventions for GBV, it is crucial that lessons and better practices from previous crises inform future response. The pathways to violence, for example, against women in prior emergency situations provides a means to streamline the process of creating effective solutions in the COVID-19 context.

Similarly, this historical context can also be used to inform priorities in policies addressing GBV, and yet, the importance of this work is not always recognized. For example, an analysis of the UNDP and UN Women Gender Response Tracker shows less than 40 percent of included policies were gender sensitive. This is crucial in addressing the structural factors contributing to GBV and other forms of violence against women. The analysis highlights a particularly stark need for inclusion of gender-sensitive policies developed in lower-income countries.

However, according to a systematic review of literature on violence against women and children during the COVID-19 pandemic, challenges with data and reporting also exist:

- Most studies find at least some increase in violence against women and/or children. Findings apply across different demographics and contexts.

- Where mixed or decreasing trends appear, evidence suggests underreporting may, at least in part, account for these results.

- Some studies examine risk factors and other dynamics around violence against women and children in the COVID-19 context, but few studies examine the impact of policies and interventions (e.g., helpline campaign in Mexico and youth empowerment programme in Bolivia).

Designing better systems to protect women from GBV

Globally, innovative measures to combat GBV and other forms of violence against women were sparked or accelerated during the pandemic. Nonetheless, gaps in understanding of the magnitude of this problem and best practices to protect women and girls have remained both during and beyond this ‘shadow pandemic’.

One fundamental theme emerging from this period is the value of digital platforms in connecting victims of GBV to supportive services through messaging and outreach, making sure policymakers recognize the existence of these events, and assuring that access to GBV-related support services increases. Nonetheless, it is crucial that responses to GBV critically evaluate digital platforms, resulting data, and even the conceptualizations of GBV in a pandemic- and digital-first setting.

Such evaluation must also focus on identifying solutions to the gender digital divide and other factors that constrain individuals in being able to report and access support for survivors. The nexus of digital technology and GBV support has great potential, but it is imperative that implementation is driven by sound data and theory, particularly regarding closing existing gaps.

- Cláudia Abreu Lopes (@cabreulopes) is a Research Fellow and Calum Handforth (@calumAH) is a Digital Health Consultant at United Nations University International Institute for Global Health (UNU-IIGH), a think tank that incorporates a gender lens in its policy-relevant analysis to inform the development, implementation, and evaluation of health programs.The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and author and may not reflect those of UNU-IIGH.